Translated from Hebrew by Aryeh Naftaly

Nurith Aviv has been involved with filmmaking for four decades and has been a cinematographer since the 1970s. She was the first female cinematography student at the Institute for Advanced Cinematographic Studies in Paris (IDHEC, now La Fémis), then became the first woman cinematographer in France and, apparently, in the whole world. She has shot about a hundred feature and documentary films with the finest directors in Israel and the world over. She shot Boaz Davidson's Shablul featuring Uri Zohar and Arik Einstein as well as many other films. She "slipped into" directing, as she puts it. Armed with endless curiosity, intellectual passion and restlessness, it was only natural that she begin to translate her own ideas into films. From translating other directors' ideas into visual language she moved on to dealing with the Hebrew language, a study that turned into an obsession and engendered her trilogy of films about the language; films on which she made her own very personal mark. Nurith's films all comprise real-life material, carefully planned and orchestrated like musical pieces. Her unique style is liable to give the false impression that they're all alike; Nurith says that they can be seen as variations on a theme, not unlike Paul Cezanne's apples, which he painted for thirty years as experiments in form, color and light.

The trilogy on the Hebrew language brought about her latest film, Annonces ["Annunciations"] (2013), which deals with the three Biblical heroines Hagar, Sarah and Mary, who prophesied about their sons.

Annonces was screened this year at a cinema in Paris for a few months in a row simultaneously with a retrospective of all her works. Another retrospective opened in December at a cinematheque in Brussels. In 2008 the Jeu de Paume Museum in Paris hosted a retrospective of all her films as well, and the Cinema South Film Festival in Sderot conducted a seminar on her work which featured articles on her films and a comprehensive interview. (This can be found on the Cinema South Festival website: http://csf.sapir.ac.il). Annonces will be released commercially in Israel in 2014 and Nurith is very excited. As we were working on this interview Nurith received a moving letter from Jeanne Favret-Saada, an important French anthropologist, which filled her with joy. She asked that we add it to the interview. We chose the main points:

I'm thrilled by the precision of what you have to say, by the beauty of the connection between image and word, by the way you distance us from our preconceptions and prejudices.

It took me a long time to get around to watching Annonces since the religious nature of the Christian Annunciation and its parallels in the Old Testament always repulsed me deeply. But here you propose the only possible secular reading: "God" is a general term for everything that inspires or enables the motion of the symbol, the word, the voice or the image. And you remove these annunciations from the context of the feminine body held captive by patriarchal concepts. All at once the great religious texts join the great literary texts as well as all the great myths ever created by man […] It's an entirely secular matter.

Why did you feel it was important to begin with Jeanne's letter?

Jeanne Favret-Saada is the important anthropologist who changed the face of French anthropology. Some people in the US say that she was the first vestige of French post-modernism. Her book "Words, Death, Destiny," which was also translated into Hebrew, (translation: Aviad Kleiman, Tel Aviv University Press, 2004) helps me overcome the concern and prejudices of sworn atheists like herself that Annonces is a film about religion or religions.

Then what is the film about?

What interests me are the texts, the myths, how they've been interpreted by different cultures and different languages and how we can continue to interpret them. I'm not interested in established religion or archeology. This is a film about motherhood and birth, but not only that of Ishmael, Isaac and Jesus. The film is about the birth of the image, the birth of the voice, the birth of the poem. It's divided into sections: Hagar – the desert; Sarah – the voice; Mary – the image, the poem. So actually the film is about the same elements that lie at the heart of filmmaking: the stories of heroes, location, image, sound… it's actually a meta-cinematic film.

How did you arrive at the subject of annunciations?

Like all my films since Circumcision (2000), each film begets the one after it. So, too, Annonces came from Traduire (2011), in which ten translators, each in his own language, spoke about translating literary texts from Hebrew. Annonces came about during the discussions on cinema. Often, after the screenings, one of the members of the audience, usually a translator, asked why I don't make a film in which a number of translators talk about a single text. Since in Talmudic Hebrew the word "to translate" also means "to interpret," I thought I'd take a text that interpreters would speak about. Thus I eventually chose three short texts that have something in common – the three annunciations of Hagar, Sarah and Mary – and asked seven women not to actually interpret them but to find associative threads in them. When I started thinking about who I'd ask to speak, I only came up with women. I guess it's mainly a question of the female voice, just as a musician writes a piece which is a variation for seven women's voices.

How did you choose the women?

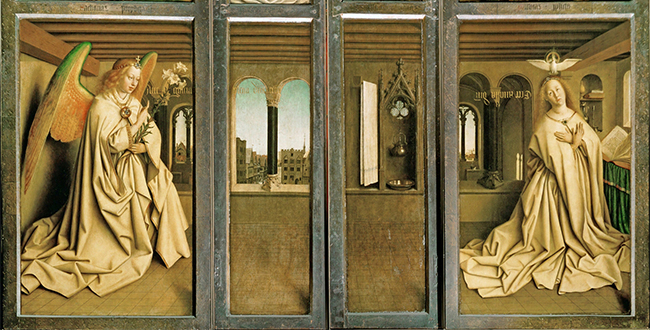

When I started thinking about who'd speak in the film I knew that Marie Gautron would have an important part in it – we've been friends for 25 years now. Marie has an amazing story: She grew up with a very religious adoptive mother who always stressed the fact that she was a virgin. Marie is an art historian. I asked her to talk about her childhood with her virgin mother in comparison with paintings of the Virgin Mary when the Holy Ghost brings her tidings of the birth of her son. It was important to me that Marie-José Mondzain, a philosopher of images and imagery, be in the film.

She's the one who emphasizes the fact that it was Christianity that permitted the figurative painting as we now know it in the Christian-Western world. Judaism forbade the depiction of God, but Christianity, through a centuries-long process, allowed the depiction of God and placed man in the center of the picture. The moment when Marie receives the Annunciation is the moment when God is embodied in the flesh in the form of the Son. God as the Son became visible, therefore the portrayal of Him is permissible and desirable. Other important art historians including Daniel Arasse, Hubert Damisch and Georges Didi-Huberman also examine this in their analyses of the paintings of the Annunciation. Godard said: When you see a truck, think of Marguerite Duras because Duras made a film called The Truck (1977). When I look at a figurative painting in the Western world I think of the Annunciation and its imagery…

The film centers around the subject of imagery. But since the film is about annunciations, I also wanted to mention the voices of the angels who bring the tidings to the women, which is how I arrived at Ruth HaCohen the musicologist. With her voice she covers a world of sounds and sparks countless associations. I found Sarah in a movie theater; she came to see my previous movie a number of times and came up to talk to me. We became friends and I found out that her mother named her Sarai, and that without knowing the Biblical story she changed her name to Sarah when she was 18. She told me she's a psychiatrist and to top it off, she works in a maternity ward. I found Rula from Lebanon through Yitzhak Nivorsky, the Yiddish-speaker in my last film. She studied Yiddish with him and now she teaches Yiddish in the US. She also speaks Hebrew, and of course Arabic and French and a few other languages. She's the one who talks about Hagar in the Bible and about Mary in the Koran. This is Haviva Pedaya's third appearance in my films – she may be a sort of lucky charm. I invited Barbara Kassen ???, a philosopher who deals with language, to speak after a screening of From Language to Language (2003). I heard her speak against the one God, against monotheism and in favor of multiple gods, the Greek gods. She also speaks about the birth of poetry. I thought that would be a good way to end the film.

How do you work with your characters?

The women portray themselves, and with each one it's a different story. I asked Marie, for example, to begin with the statement she once said to me: "My mother was always telling me she was a virgin." I suggested that as the opening statement and I told her to go from her own story to the paintings of the Annunciation to Mary. We chose the paintings for the film together from hundreds, maybe thousands of paintings of which the Annunciation is the subject. But I wondered how she'd transition back from paintings of the Virgin Mary to the big surprise at the end, and she did it wonderfully. In Marie-José's case I started to read her very complex books and it took me a whole year. I had to choose what I wanted her to talk about from amongst the tremendous amount of material she's written. I worked out the points I wanted her to touch on and gave her the list. Later I found out that her father, a Jew from the ghetto, was thrown out of his father's house because he wanted to be a painter. I realized that if I asked Marie-José, a very intellectual theoretician, to begin by talking about her father, it would help her open her up emotionally and might also explain her choice, as a philosopher, to deal with images and imagery. I asked Sarah to connect the Biblical story of Sarah to her own personal story as well as to a clinical case from the hospital where she works. She made the connection through the Biblical Sarah's laughter and the embarrassed laughter of a patient of hers. I feel it's important to connect the theoretical world with the speakers' emotional worlds. As I see it, the flow of thought has to do with the subterranean streams of emotions and passions.

They say you make all the decisions, even what the speakers wear.

I'm not looking for documentary naturalism; it's more like theater in which the stage is the film itself. That's why the film opens with Rula, who's filmed on a theater stage in a red dress, the most common color of Mary's robe in Renaissance paintings. In this film I wanted the women to all look pretty; we put a lot of effort into the cinematography and lighting as well as the choice of clothing. I'll give you an example: Haviva Pedaya suggested wearing red, which looked very pretty in the desert where I filmed her walking, but since the wall I chose in her house is yellow it didn't go with the red of the blouse she suggested. With Ruth HaCohen we decided on one blouse during preparations, and on the shooting day she chose another blouse, in blue. It reminded me of the angel Gabriel's blue robe in paintings of the Annunciation. I thought it was perfect. I don't only relate to the color of the garment of each woman individually but to the general color theme of the whole film and of one in relation to the other.

Could it be said that your first films were more political?

In the case of the first two films I made, Kafr Qara, Israel and The European Tribe, production companies contacted me asking me to shoot films by people who don't come from the field of cinema, so I ended up directing them as well. With the film Work, Place (1998) I was contacted directly by a Jewish producer who was intrigued by the phenomenon of African foreign workers at the Tel Aviv Central Bus Station. In the end it turned into a completely different movie without her, about the Triangle [an area in north-central Israel which includes the Green Line]: Israelis, Palestinians and Thai workers on a Moshav [Israeli farming village]. These films definitely centered around the political aspect. I consider the films that came afterwards, which I initiated, political on a deeper, more hidden level. For instance the film Circumcision: Jews and Muslim Arabs are on the same side in terms of the tradition of circumcision, as opposed to those who come from the Christian tradition and don't circumcise their sons. Circumcision deals with mixed couples, and what I was interested in wasn't the actual circumcision but the discourse and mainly the emotion that the issue involves for mixed couples, whether or not to circumcise their son, whether to preserve the generations-old tradition or forego it. This is the question that also concerned me in my next film, From Language to Language (2003) – does the parents' generation pass its mother tongue on to the next generation or forego it? This film is about the tension between the language spoken at home – the language of emotion – and the acquired language in which, in the case of the participants in the film, the authors and poets write. Like the films that came after it, this film talks about Zionism and its results from a critical point of view, although that isn't the subject of the film.

Then could it be said that one of the main questions you ask in your films is the question of transmission from generation to generation?

Yes, the question is what is preserved and what is lost. That, of course, is the question in Loss (2002), which deals with the cultural vacuum that the Jews left in Germany after the Holocaust. In From Language to Language authors and poets who write in Hebrew talk about their other language, the one called their "mother tongue," which in many cases they've repressed, rejected or forgotten. In Langue Sacrée, Langue Parlee (2008) as well, I address writers and try to find out what role the Holy Language plays in the spoken language in which they write, what's new, what's preserved, how much is preserved.

How did you end up with this near-obsession with language? Did you plan to make a trilogy about language?

I've always been interested in language, because, among other things, I was raised with two languages – German and Hebrew. Furthermore, for forty years now I've lived between Paris and Tel Aviv, between Hebrew and French. I've also undergone psychoanalysis – in French. And in my case, since I dream in four languages – Hebrew, French, English and German – I have lots of dreams with multilingual puns. Surprising connections between the languages come up in these dreams. The transition from language to language fascinates me, which is how I ended up doing From Language to Language. I didn't know it would be a trilogy. From Language to Language led to Langue Sacrée, Langue Parlee, which led to Traduire (2011), which led to Annonces.

How do you start to work on a film?

I always begin with a subject that interests me and I think will be fun to think about and work on for the next two years. I read endlessly and buy loads of books, and then I start to put together people, ideas, texts and images. At the same time I'm constantly dealing with the question of style.

You create boundaries and limitations for yourself.

I work within boundaries and restrictions that I create for myself, for instance, that there will only be women in Annonces, or that only native Israeli Hebrew-speakers would appear in Langue Sacrée, Langue Parlee, or that each of the translators in Traduire would speak a different language and that their order of appearance would be dictated by the chronological-historical order of the Hebrew source they talk about. The amount of time each speaker has is also predetermined. These restrictions enable me to find a more concise, precise style and pace, sort of like a musical structure.

You speak a lot about your rigorous preparations before every shooting day, but still you like the happenstance that slips in.

That's right. When I start shooting, most of what I'm doing is planned in advance. But that's exactly why I'm willing to turn everything upside-down on the day of the shoot. I like to leave everything open, to change my mind. It's a constant tension between a very precise structure and a constant expectation of encountering the unforeseen which comes as a gift. It's precisely when I know exactly what I'm looking for that I'm more willing to accept the surprises that reality brings to the table.

You're a director with the eyes of a cinematographer or a cinematographer with a director's approach. Can you talk about the reciprocal relationship between the two approaches?

As a cinematographer what has always interested me is the language of filmmaking. I've always seen myself as a translator, as someone who conveys the director's ideas and desires to the camera, to the lighting. Since I started to direct, especially since the film Circumcision, I've actually dealt with the same thing, except that the ideas, desires and passions are my own. These are subjects that interest me and over the years have even turned into obsessions. The transition to directing was almost unnoticeable because I continued to film for other people. Only in recent years have I stopped filming for others and mostly directed. But deep inside I really feel like a cinematographer and I feel like that's my strength when I approach directing. That feeling doesn't fade with the years; on the contrary.

In your films there's a lot of talking but the scenery plays a central role.

I'm very attached to my childhood, to the Hebrew language and the landscapes of Israel. It's an elemental, very emotional attachment, and the time I spend away from the language and the place actually increases the attachment. This, I suppose, is the reason for the strong presence of the landscapes in films I've shot in Israel. The landscapes I shoot abroad are also a reference to the elemental landscapes of my childhood, if only because they're so different.

Do you define your films as documentary?

I don't know how to define them, exactly. They aren't naturalistic films; fundamentally they're staged and very planned-out. The same is true of the talking in my latest films; they aren't really interviews, they're more a sort of 5- to 7-minute performance which those who are willing to play along do very skillfully. This can take months of dialogue to achieve. It's important to me to find the pace and style of each film even if it sometimes seems like a repetitive game, because for me it's totally new every time. I'm talking about style and tempo, not just something that's "beautifully filmed" but in which cinematic language the cinematography speaks. In many films the important thing is a strong, touching story, and the question of how to translate it into cinema isn't always the main question and the difference between a good documentary and good reportage isn't always clear. In Israel, content is very important and it supersedes form. I remember, when I edited Work, Place in Israel I felt like I had to give it a fast pace although it wasn't the pace at which the film was shot. I think it has to do with the atmosphere in Israel, everything's so intense, fast, there's no time, no patience.

It seems like your direction doesn't end when the film ends; you continue to direct at the screenings.

A discussion is held three times a week at a movie theater in Paris with someone I invite – an author, artist, philosopher, psychoanalyst. So between thirty and forty people were invited to screenings of every one of my films. I feel this is an integral part of the project as a whole. This is especially true of Annonces. At the heart of it is the film in which there are three annunciations (from the Old Testament, the New Testament and the Koran, in Hebrew, Greek and Arabic). Seven women address these texts in the film, find threads in the text and create a new, very musical tapestry. In the theater the people I invite to moderate the discussion join in, and the viewers also comment during the discussion. We film every discussion and post it on my website. If you look at the discussions page on the website you can see that they're set up visually like a page of the Talmud – in the center is a picture of the film with commentaries all around it. It's like an art installation.