The Grey Area of Truth

Anat Even & Ran Tal

Michal Aviad has been a political, feminist filmmaker since the outset of her career. In her films she studies Israeli society through a prism of gender, shifting freely between a variety of creative and expressive styles. "My way to develop an idea is by forming a cinematic language for the particular film." She shifts between first-person films, observational films, fly-on-the-wall films, and has recently begun to create dramatic films as well.

Her first feature film, "Invisible," featured authentic documentary footage, and in her latest film, "Dimona Twist," winner of the Haggiag Award at the last Jerusalem Film Festival, she included "archive-like" footage. Her work in recent years has become more hybrid; films based on reality no longer satisfy her and she continues to challenge herself with a search for a cinematic oeuvre that conveys her intentions more precisely. In her hybrid films she doesn't address the issue of truth since in her eyes every film constructed of footage from reality is staged. The truth as she sees it and to which she is committed comes mainly from her loyalty to herself as an artist.

Michal, let's start from the beginning. Since your very first film you've dealt with women, and you may be the most consistent film director when it comes to that. Can you talk about how you started out, why you kept going and why you're still doing it?

When I went to San Francisco in 1981 to get my MA degree in filmmaking I already had a BA in literature and philosophy and I was ripe for seeing the urgency of the struggle for women's liberation. Once there, within a week I realized that I'm a feminist. In San Francisco of 1981 feminism and gay-lesbian liberation were the most revolutionary and exciting things imaginable. Back in Israel I'd been an activist against the occupation and I took part in the struggles, and the baggage I brought with me fit in perfectly with what I saw on the streets of San Francisco. At university I was also exposed to the revolution of the feminist film theorists. It began with Laura Mulvey and extended to include other fields of study. When I studied there at least half of what we read was feminist film theory. Chantal Akerman's film Jeanne Dielman really shook me up, as did other films that brought a new cinematic language to films by women directors. Granted, my first student film wasn't about women, it dealt with Mexican immigrant youth. But by my second student film I was dealing with women. I think that from film to film I understand better and better that the prism through which I see, both as a woman and as a filmmaker, shifts the lens in a certain sense, and suddenly the world that's revealed to us is different from what we're used to seeing. Our lives as revealed through women's eyes strike me anew every time. This continues to challenge my understanding of reality and of filmmaking.

You mentioned a political moment and a theoretical moment that you connected to. You could have connected to other moments, to other political places that arose at the time. Why feminism in particular?

I was a young woman, I'd been involved in a wide range of political causes, I knew what the occupation meant, and I was somehow connected to the claims of the Black Panthers. I was angered by mechanisms that create power struggles on both the theoretical and activist levels. Feminism fell into this like a ripe fruit. If you care about human rights you realize that women's rights are part of the equation. When you see people who suffer injustice on a daily basis you realize that women, including you, are victims of injustice.

You've been dealing with women for 30 years now.

It started with the first full-length film that I made in the States back in 1987 called Acting Our Age. It features six women, all over the age of 65. It deals with questions of aging among women and how aging among women is perceived and experienced by society differently from that of men, on the economic level, the level of self-perception and the family/social level.

A few years later I realized that the film I made belonged to a certain generation. It was a particularly feminist moment in the deeper sense when it was realized that the individual is political. Men and women started to grab cameras and film people, film the common and differing experiences of people in certain fields or on certain subjects. I chose six women, and typically of the period there was one black woman, one Jew, one Mexican, one lesbian and so on, and I gave each of them a voice. They were all unknown. Suddenly anonymous women were talking about aging. The film was a big success. It competed at Sundance and opened the first season of POV, the annual series of documentary films on PBS. Only years later did I realize I was working within a period genre. But it was truly new at the time, new in the sense that we no longer needed experts to tell us how to understand our lives. I think the feminist concept that the personal is political, which manifested in our films again and again, paved the way for a new era in documentary cinema which was a pleasure to get into, it was exhilarating. I now see how my first film relates to my latest, to Dimona Twist.

You seem to be the Israeli woman director who has most devoted her work to feminist issues, you return to them time and again, and the question is whether beyond your intellectual and political identification there's something else that makes your work especially significant within the frame of womanhood.

I don't think I make films about subjects which are "within the frame of womanhood" or films that concern only or specifically women. And I don't devote my films exclusively to feminist or women's issues. I have no films that deal, for instance, with important issues like pregnancy and birth or weight issues or a million other issues that are super relevant and super important. I "genderize" questions that concern me – if you ask me, you can look at any subject from a gender-oriented point of view. I make films that ask questions about women's and men's lives through the prism of women. It's not the same thing.

You made your second film in Israel and it deals with the occupation, through the female prism once again. How did it come about?

In the late '80s my first son was born and we also wanted to come back to Israel. I was a young mother and the question whether my son would be a soldier serving the occupation really worried me – the occupation was in my bones. I went to the West Bank in the summer of 1989, during the first intifada, before we even moved back to Israel. On the Palestinian side it was women who spearheaded the struggle and the leadership of the four Palestinian factions worked together for both national and women's liberation. That led to my film The Women Next Door (1992) which deals with the involvement of Israeli and Palestinian women in the occupation. The next step was Ever Shot Anyone? (1995) which was a continuation of The Women Next Door, of course.

I think I started to realize that if I step back and think as a woman I see something new. As Israelis we always need to make a huge effort to think objectively. And after many, many years abroad I'd go to the corner store and look at the queue and wonder: Did the men here kill people? It's an experience I've never had and never will. It drove me crazy and it still does. We're so trapped in our nationalist way of thinking, not only here but in other countries too, that when war is perceived as being justified, everything is justified and people have to be killed and everything else it entails. It's a very deep-rooted part of human civilization. And since the fact is that it's mostly men who make war, men have to get used to the idea of killing people from the time they're born. Ever Shot Anyone? deals with the culture of men in Israel through my joining a reserves unit in the Golan Heights.

There's something about feminist thinking that gives one a fresh viewpoint, a different way of seeing things. It's not only feminist thinking, it's also thinking that insists on looking at reality beyond the Jewish-Zionist paradigm. Maintaining objectivity, maintaining independence. It's an attempt to define where I'm at, or what lifestyle I want to lead. That film began with my fascination with men and my fascination with men who serve in the army and are part of the mainstream of Israeli society. What concerned me as I was working on it was the fact that the men thought my questions were really funny and the film basically turned into a comedy because they kept laughing at me.

By these films you're present in first person, then you made "Jenny and Jenny" which follows the lives of two teenage girls from Bat-Yam, a realistic fly-on-the-wall style film. From there you move on to "For My Children," another first-person film, then "Ramleh." You shift between different documentary styles. How do you decide on the style and the cinematic language for each film?

The ideas for my films come out of nowhere, that is, they come from inside me and at first I don't even know where they came from or why. My way of developing an idea is through molding the cinematic language for the particular film. This happens as I do the research. I'm not interested in repeating a cinematic style I've done before, so in order to hone my skills I try different ways of expressing myself. Soon enough the form and content intertwine and it becomes clear to me that this is the way to make this specific film. The Women Next Door was my first first-person film and in Ever Shot Anyone? the conflict within the film takes place through my presence in it, and there I realized how cool home video footage is. The soldiers and I were the same age, and my involvement allowed me to film and address things I found interesting and tell a different story than other army reserves films tell. In Jenny and Jenny I wanted to make a film packed with the girls' energy and hormones and I played no part in it. In Ramleh I experimented with a film with no interviews; I hoped for a film in which the story tells itself. Later I added personal narration because I needed to express aloud what I didn't express through the protagonists. For My Children utilizes personal and public archives for the first time, and so on. I'm not interested in repeating a cinematic form, although I really admire directors who hone a form they invented more and more.

You said that your first film relates to your latest, "Dimona Twist," so maybe this is the time to discuss it. Can you tell us how it came about?

Dimona Twist (2016), like Acting Our Age from 1987, revolves around a few anonymous elderly women. In both films there's no narration and the women tell their stories on camera. Maybe that's where the similarity ends. Even today, just as then, there aren't many films that let old women talk about themselves.

Dimona Twist is my second historical film. It was preceded by The Women Pioneers (2013) which dealt with the story of the immigrants through the diaries of women from the Third Wave of Immigration. They tell of the pain they experienced in Ein Harod when they realized that the agenda they came with – to create a new, independent woman who doesn't only serve the men's needs – was doomed to failure. The Women Pioneers combines readings from the diaries with period archive footage.

This time I wanted to focus on the Great Immigration, on a development town in the south. I wanted to understand exactly what happened, to leave behind the fruitless debate about who suffered more, the Ashkenazis or the Sephardis, and deal with the way people experienced immigration to Israel. Through my years of filmmaking I'd visited Dimona, Yeruham and Netivot several times – schools, community centers, nursing homes, here and there. A traveling merchant who goes from place to place and talks to audiences after screenings. I chose Dimona because I found more archive footage with it than other development towns. I went to Dimona with a researcher and we spoke to women as we learned about the history, the press, the academic studies, the correspondence between the establishment in central Israel and its representatives in Dimona, the archive footage and the stills.

As I was working on it, people around me told me I was getting into the hottest, most virulently debated topic on the Israeli agenda. And I was very worried. We spoke to many, many women. I'd been to Dimona many times; not only Dimona since I wasn't only interested in women living currently in Dimona, I was interested in women who lived in Dimona back then. One of the most significant things I learned as I went along was that as people grow old, and I assumed that this includes me, we prefer to see the hardships we've been through as factors that strengthened us and gave our lives meaning. Most of the women I met had made peace with their past; with the immigration, with Dimona, with the establishment, with their families. I learned that from this perspective, as a memoire, that is, unlike a journalistic report from the present, no life is devoid of meaning. Even if you dreamt of Paris and landed in Dimona against your will, at the end of your life the anger dissipates and if you're lucky you make peace with your fate and your life.

Now at screenings of the film people ask me: "How did you invent such strong women?" "It's surprising to see that they aren't bitter." These two comments are liable to contain a hint of condescension. Bitterness is a personal, not an ethnic trait, and not a particularly endearing one at that. Bitterness isn't anger. And "strong" wasn't a characteristic I was looking for among the women. I was looking for women who have something to say, women who think for themselves, opinionated women. And as for "bitter," when I look at how the film came to be, there were women who wanted to be in it but their husbands or children wouldn't let them. The protagonists of documentary films live in communities, and it's clear to me that the protagonists' communities have to accept their participation as well. But only after I finished making the film did I realize that of the seven women in the film, six, I think, were either widowed or divorced. And that brings us back to the subject of women. It turns out that women attain a certain independence after they're widowed or divorced, and maybe only then do some of us become opinionated.

At a certain point in your work you start to work with archives. The love of archive footage is very apparent in your films; as early as "For My Children" you use archive footage, then in "The Women Pioneers" which is constructed entirely from archive footage. Can you discuss your connection with or your love for archives?

A side of me is an "archive mouse." I love to sit in archives from morning till night and look at footage. It totally turns me on, the connection between the personal and the public, the personal and the historical. For instance, when I was looking for material for For My Children I discovered that in March of 1938 Mussolini was in Trieste, which is the city where my mother was born. Just before his trip he issued the racial laws. Now, my mother had told me since I was a child that she went to watch Mussolini drive down the main street. She was a schoolgirl, and for her it was like going to see a superstar, the mega-celebrity she was raised on, the hero who had just betrayed her. When I saw the footage I suddenly connected with that specific experience that happened to be my mother's. The realization that there were little people who were crushed by history, influenced by history, changed by history. That adds depth to who we are today. My cinematic work and my work in general is concerned with what molds us, in which way it's our psychology, our families, our sociopolitical environment, our status, our gender – all these things come together when you deal with archive material, they're actually glued together. So for me, the essence of the experience of rummaging through archive material is finding the moments that illuminate how this happens.

In essence, you give the material a new meaning. And in "Dimona Twist" you decide to create an archive, that is, you recreate the period. Why is this so important to you?

While researching my film about Dimona I found four newsreels about senior government ministers coming to Dimona. In one, Golda Meir comes to Dimona – she was Minister of Labor or Housing – and she comes to lay the cornerstone for the school to be built in Dimona. This is half a year after the first citizens moved to Dimona. Only after you watch this footage ten times do you realize that all the people there are American donors and all sorts of dignitaries that she brought to Dimona with her who donated a little money to develop the city, and the people who live in Dimona, who should be the center of attention, are on the fringes.

Why doesn't that appear in the film?

It isn't in the film because that footage had nothing to do with any of the women who participated in a way that would justify its inclusion. Overall, I found very little footage that documented the stories I heard in any way. When I watched the films that were made, and luckily there were two lovely films both of which were released in 1962, both government-sponsored propaganda films, I saw that there were hardly any women in them. The government wanted to show construction and growth, so you see builders building, and the women, who generally work indoors, hardly appear in the films. What the women told me about how they dressed, where they went, what they ate and what they did, barely exists in the footage that was filmed back then. History was erased. Moreover, the Dimonans weren't middle-class people and they didn't have Super-8 cameras. I felt that if I wanted to restore them to history the only way would be to create it myself from what I understood from their stories.

Within the language of the film I knew from the start that what I wanted to do, as with The Women Pioneers, was to take them back to the old days. That's why I didn't focus on the protagonists as grandmothers or on their relationships with their children and grandchildren or the apartments they live in now, who's rich and who's poor, who still lives in Dimona and who lives in Ashdod or Rehovot. I wanted to be totally there, in the period. That's why the conversations with the protagonists took place "beyond time," outside of their current living conditions. That's why I mixed archive footage with footage that we shot that looks like period footage.

If you weren't familiar with the period footage, what did you base the scenes on?

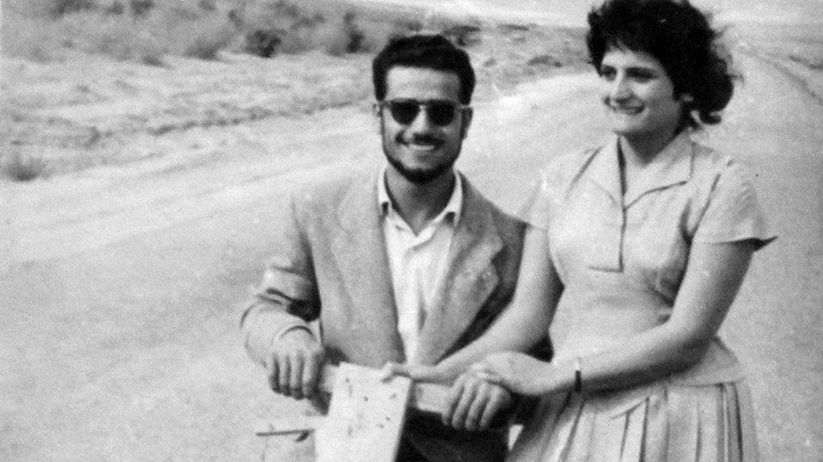

Itay Marom and I did two things. First of all, we did serious research into what and how they filmed in Super-8 in the '60s. We watched Super-8 films and saw that they filmed people looking at the camera just like in home videos from the '80s and '90s. Then I invented a character, I decided there was a woman named Josianne who moved to France with her family but her aunts and nieces moved to Dimona. And since she's in France and she has more money, she brings a Super-8 camera to her vacation in Dimona in 1965 and she films her nieces and friends and so on. So we filmed only what she would have seen, what she might have filmed to show her family back in France. We tried very hard to do shots similar to those that amateur photographers would have done back then. The content was stories that the protagonists told but weren't included in the film. So on the production level it was really strange, on one hand we had a crew for a feature film, a costumer, an art director and so on, but on the other hand the makeup artist didn't do makeup, she only did hairstyling, and there was no sound. We also created a sort of hybrid within the production itself in terms of how fictional films are made and how documentaries are made, that is, it was very thought-out, what the scene we're shooting is about, why we're shooting the scene, what we're trying to convey, and mainly what the guest from France would have filmed. It's a sort of fantasy as well as a way to include stories that didn't make it into the film.

You talk about mixing genres, which is very typical of your recent work. Before "Dimona Twist" you made a feature film based on your own life story and interspersed it with documentary archive footage. That is, in recent years you've moved from dramatic to documentary filmmaking and your documentaries are becoming more and more hybrid. Do you have ethical questions regarding hybrid cinema, and why do you feel ever more comfortable with it?

On the ethical level of documentary cinema I really relate to an article by Yigal Burstein in the Cinematheque magazine from many years ago. It was an abridged version of a longer article by him. He wrote that like it or not, we as cinema-goers demand an aura of truth. That's how he described it, although I'm probably misquoting a little. That is, although everyone knows that documentary films are directed, that they interpret the truth, viewers need to believe in that aura that testifies to some proximity to truth.

In Ramleh I realized there's a limitation to documentary filmmaking. My protagonists had full lives that didn't appear in the film because they didn't want them to. For instance, one of the supporting characters, a member of Shas (a Sephardic-Jewish religious party), her father is an Arab. They have a wonderful relationship but she didn't want us to mention it in the film. Why not? Because she has relatives in Ofakim (a Jewish town) who don't really know, as well as relatives in Tira (an Arab town) who don't really know… Anyway, she didn't want it to be in the film. Another woman's brother is a criminal, a serious drug dealer, and it was clear to me that I had to leave him out. So there are parts of reality that documentary cinema has to leave alone. We have to leave the underworld alone. Documentary cinema can't really go into corruption. Then I realized that I'm not really telling the truth when I make a documentary, THE truth as I see it, as I know it. Not an objective truth; I'm not telling the truth I'm committed to if I'm faithful to myself as a film director. In documentary filmmaking I'm often unable to tell the truth since I have to protect the people in the films, because people always come first. Then I have to lie in order to be loyal to people. And concealment is often lying.

Or only part of the truth.

Right. But if I told the whole truth it would change the story.

If you could look at it from a historical-political perspective, what does it mean that cinema based on real-life footage disappoints you in a sense, so you look for a new language, a new technique in order to get to the truth?

It's very simple. It means that purist documentary filmmaking is limited in its ability to portray reality as I see it. Still, it was important to me to write at the end of Dimona Twist, even if no one read it, that the recreated Super-8 footage was made by all those people, to write the names of all the extras, the names of artists involved, and I would demand the same of anyone else, since even if the untrained viewer can't tell the difference, it's my duty to provide the answers.

Hybrid cinema has become very fashionable, we all do it, but here we enter a certain grey zone…

Totally. We documentary filmmakers know very well that if we tell someone: "That shot didn't work, go outside, open the door and come in again," or take him to places he wouldn't necessarily go, or pay him to fly to Ethiopia to visit his parents… we're interfering with reality, if only for structural purposes. By the very fact that we put a camera there, decide on the angle, cut and edit the footage and so on, we're constantly creating reality through filmmaking, even the ostensibly purest documentary cinema.

Documentary filmmaking addresses the questions of hybrid cinema all the time, but fictional cinema doesn't address documentary cinema. What do I mean? That from its inception, fictional cinema has always used documentary techniques and means of expression. They're subjugated to the purposes of fictional cinema and nobody asks questions. All is well. But documentary cinema is constantly concerned with these questions. From Italian neo-realism through Cassavetes and Dogme films and Ulrich Seidl and the Dardenne brothers and all sorts of admixtures, I examine films that transition between documentary and drama. Sometimes the set is the street with the people in it, sometimes there's no script or the actors are non-actors. Sometimes the admixture is between the actor and the character. Fictional cinema has always incorporated documentary elements, from its very outset. Nobody says "tsk-tsk, you're crossing boundaries." The aura of truth is sometimes created by a long shot, since there are less cuts which makes it feel like a bigger chunk of reality. Now when I watch 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (Cristian Mungiu) the sense of reality is created by the long shot. This is why documentary films and realistic fictional films always go together in my eyes. After all, from the first day I started to make films I created events, inserted my protagonists into them and filmed them.

At a certain point in your career you decided to make a feature film. How did that happen?

After I'd made Ramleh and then For My Children I felt the limitations of documentary filmmaking, that in documentary cinema we can do two main things: One, talk about what happened, i.e. interview, discuss, as in Domino Twist, and two, follow what's happening in the present. These two options don't allow me to do what I wanted to do in Invisible, which was to talk about a long-term trauma, a trauma that resurfaces 20 years on. In a documentary there were only two ways I could do this: Interview Michal and the other women who were raped by the same polite rapist about what happened and also include the footage in Invisible about the man. Then each of them would have had to talk about what she went through, her trauma, her post-trauma, and so on. It seemed to me that to connect the person with the experience wasn't at all sufficient. I wanted to show how such a thing happens along with all the nuances of how it happens. I thought, since I was raped, since I know what it's like, since I know what a resurfacing trauma is like, I know how to tell the story of how it happens. I got together with Tal Omer, who was also raped by the same serial rapist, and the two of us wrote a fictional screenplay. I knew from the start that I wanted it to be very close, that the boundaries between it and a documentary should be blurred in certain places.

How do you transition from directing documentaries to directing feature films? What was it like for you?

I really enjoyed it. It seems to me I always direct the same thing, that is, I direct through my relationship with people, and with Invisible I directed through my relationship with Ronit (Elkabetz) and Evgenia (Dodina).

Feature filmmaking can be incredibly fun. The fact that you can concentrate solely on directing, which a documentary filmmaker can never do. It's freeing, almost healing. God, what a pleasure that I don't have to tell the crew member to turn off his mobile, and make sure everyone gets fed, and I'm not expected to do anything but direct the film. So on that level it was a treat.

How do you work with other crew members and what do you find infuriating?

For me, working as a director always means working within a relationship. It's very hard to carry a film alone. So while I'm working I'm very intimate with the cinematographer and the editor and the producer and the researcher. In every film, at every stage of making the film, I'm connected with one of the film's co-creators: the researcher before production, the cinematographer during production, the editor after production, the producers the whole way through… and we carry on an intensive relationship in which we invest part of ourselves and our lives and they go into the film. Then each of us moves on to the next film. Editors like Era Lapid, Tali Helter, (the late) Danny Yitzhaki, Erez Lauffer and now Nili Feller totally saved me when I felt confused and wanted to give up. Together we found the way out. The DNA of their world blended with mine into the film. The cinematographers created an amalgam of what I managed to explain that I wanted and their unique signature of how they see the world. The fact is, sometimes the people I work with have a deeper, more precise understanding than my husband, my children or my friends of what I'm trying to do, where I fall short, what the difficulties are and what the possibilities are – their passion burns within me and my passion burns within them. Sometimes these are difficult relationships but they mean a lot to me.

And now you're working on a new feature film. Can you tell us something about it?

Not yet…

Thank you and good luck.