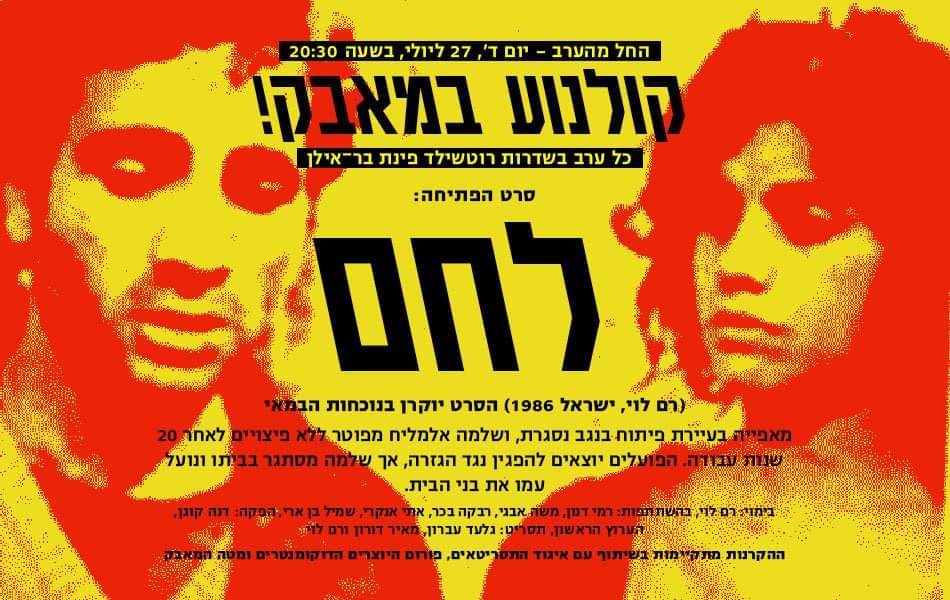

Interview with Ram Loevy

Interviewers: Anat Even and Danny Muggia

Translated by Tal Haran

The impressive body of work by Ram Loevy, one of Israel’s prominent filmmakers and recipient of the prestigious Israel Media Award, exposes the challenge he has taken upon himself, to peel reality away and direct one’s gaze to the inobvious. His humanist world view, formed early at his parents’ dinner table, moved him from his beginnings towards the muted, the denied and the hidden in Israeli society.

His world view and social-political commitment moved him from his very beginnings in Kol Yisrael, ‘The Voice of Israel’ radio, with programs addressing Arab society, and later on to films he made under the auspices of the Israel Broadcasting Authority. In 1966, the film I Ahmad – (directed by Avshalom Katz) which he produced and took part in writing its script – was the first on Israeli film and TV screens to show a Palestinian. The film immediately raised strong opposition in the Broadcasting Authority as well as among its spectators.

Most of his life, Ram Loevy worked and created within Israeli TV’s Channel 1, and in this established territory still managed to make controversial, even dissident films that actually shook the ground. Years before Miri Regev emerged as Minister of Culture, his films were censured, leading to loud arguments at the Knesset (Israel’s parliament), banned for screening on local television and even produced threats of being fired – and he persisted in producing films whose stories have burned in his heart. “The Jewish-Arab issue has been central to my work, but not the only one”, he says.

Ram Loevy has made about 70 feature and documentary films. His work revolves around the realistic and theatrical as well as the real and symbolic, but common to most of them is the gaze at the suffering of the others.

For the issue of Takriv that addresses resistant film, we chose to meet him and try to understand how one can make films that are almost a sharp provocation of the hegemonic establishment while working inside it. We met on a winter morning, on the balcony of his home in Ramat Gan. “The light is so beautiful today”, he said excitedly.

Rami, for about 30 years you worked for the state TV’s Channel 1 and managed to raise public and political storms. You are signatory to the films I Ahmad (1966), Barricades (1969), Khirbet Khize (1978), The Film that Wasn’t (1994), more and more films that sowed great unease here. Let’s begin with the question how you managed to make such films within the state channel framework?

With your permission, a few words about my father, journalist Theodor Loevy. He worked in Germany and Poland as a reporter for a network of international papers, among them the Hearst chain. He edited the Jewish newspaper Danziger Echo which was published in the 1930s in the German city of Danzig. He often found himself in conflict with the authorities. In one case, following things he had written, he was arrested and sent to a Nazi prison. Upon his release, all he told his friends was: “The food in jail was not very good…” That’s all he said. Indeed, the arrest took place a few years prior to the ripening of the ‘final solution’, but this ironic phrase was the understatement of the year.

My father and mother, Zhota (Aliza) neé Schneiberg, came to Palestine-Eretz Yisrael in April 1940, during the Second World War. I was born about 4 months later, in Tel Aviv. During the lively 1950s, our family parliament convened almost daily at lunchtime. Between soup and dessert, we held stormy political arguments. My mother was a fervent Zionist, my younger sister (Gabi, Gabriela) – rebellious and loved, and I – a devout member of the Scouts (Dizengoff Chapter), filled with national and social ideals. Dad sat opposite us. He contradicted every fraction of an idea, ideal, or fact that I drew from my elementary school (Ha-Carmel) or high school (municipal high school 1), and especially from being a member of the Scouts movement. This polyphony was responsible for my becoming who I am.

How did you become a filmmaker?

Just a moment… This, too, is relevant to your question. I was in the group enlisted in the Nahal paratroopers, and we did our kibbutz training at Kibbutz Gal’ed and at Sde Boker. I was a Scouts counsellor-emissary. Along with four other counsellor-emissaries we tried to generate change in the movement’s platform, weed out fake values such as education towards communal kibbutz life as the only way to realize ideals. We were ahead of our time, failed, and were dismissed as counsellors. One of those four, Tzipa neé Rotlevy, is a Loevy to this day…

When I finished my army service, I studied economics and political science at the Hebrew University, Jerusalem. I worked my way through my studies doing two jobs – at the Economic Planning Authority, and in the Youth Department of Kol Yisrael.

Still, how did you become a filmmaker?

Fellini’s Eight and a Half. I saw it and was thrilled. I watched the film four or five times and made up my mind: I’d give up economics. I will make films.

In the early 1960s Miriam Harman, director of the radio’s youth programs, let me edit programs whose purpose was to make Israeli youth get to know and grow closer to the Arab world, thus removing some of the monstrous stigma that we associated with it. This is how the following programs were created:

- A 10-part program called “Two Points and a Line”, dealing with Arab society outside Israel’s borders. These included programs about the status of the Arab woman, Arab music, building the Aswan dam, refugee camps in Jordan, and more. The part that caused the program to be taken off the air dealt with the childhood of Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser. I did rely on a book that was published by Maarachot, the Israeli army’s publishing house, but Nasser was then Israel’s greatest enemy, his effigies were burnt at Lag Ba’Omer campfires, and the rest of the series was cancelled.

- About a year or two later, I was allowed to make a 6-part series about Arab youth in the country – called “My Village, Your City” – about inter-generational relations inside the Arab village, relations between boys and girls, and more. The narrator of these programs was Ahmad Saber Massarwah. Eventually a lawyer and head of the Tayibe local council. Ahmad Saber and I, creators of this series, were awarded the Kol Yisrael Ahmad Saber passed away several years ago. A terrible loss.

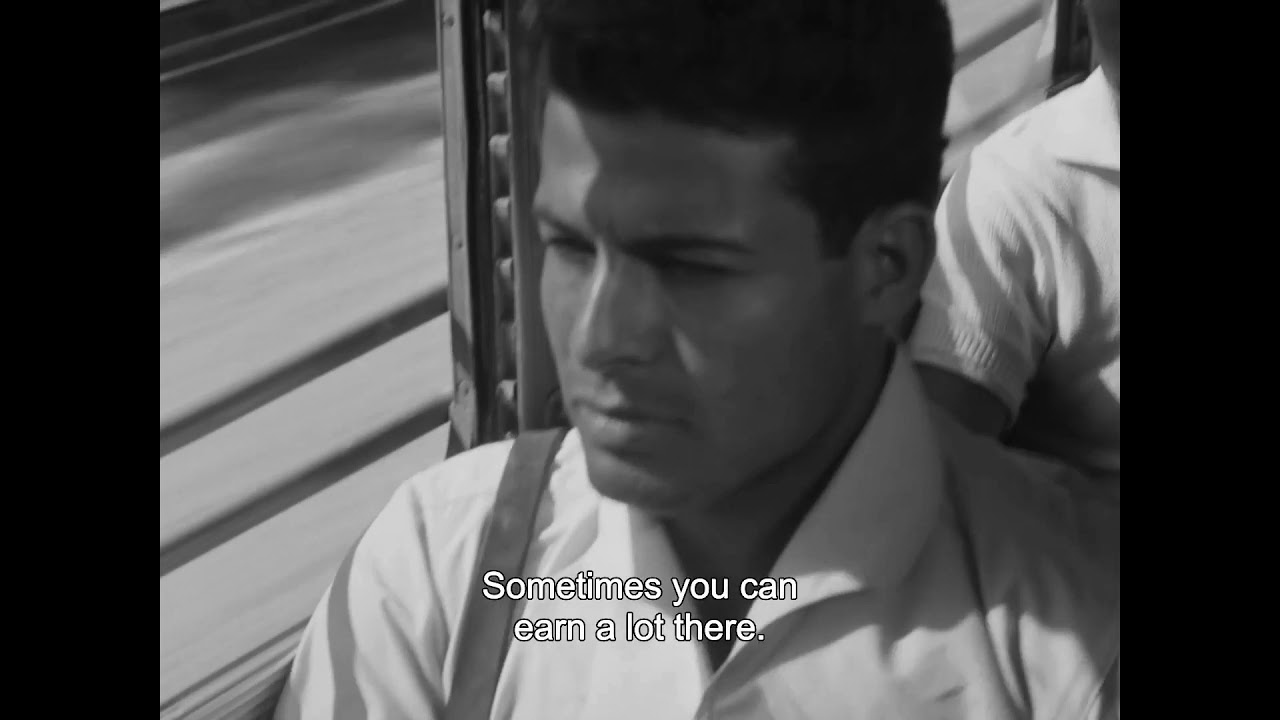

One of these radio programs was the basis on which I produced the film

I Ahmad, directed by Avshalom Katz. It was the story of an Arab boy who leaves the village to work in a Hebrew city (I was acting producer and co-scriptwriter). The main character in the film, as in the radio program, was Ahmad Yusef Massarwah from Ar’ara. Ahmad Yusef has been – and is to this day – a social leader in his village, and is one of my good friends.

How did you end up with these topics? What connected you to them as early as the 1960s?

I am not sure. Probably because of the question marks I placed on the threshold of a dominant ideology. I recall that close to the time when I began to work on one of the radio series, a demonstration was organized in Jerusalem, protesting the Military Government. I decided to join it. Because one must. Something in me shouted that I was risking my radio programs and that they are much more important than taking part in that demonstration. I decided I would go to the demonstration, but not participate. I’d stand aside. And so I did. But I realized that nearly all the demonstrators were Arabs. This can’t be! I joined the marchers. Then quite quickly someone handed me a banner, and someone else jumped me and tore the banner away, and a cameraman from Geva (or Hertzliya) newsreels happened to perpetuate the moment that was screened in cinema houses throughout the country a week later. Everyone saw this. I was sure that this was the end. Because of a moment’s stupidity I’d lose my job at the radio. I sat and waited for the phone call that would throw me down all the stairs, and indeed Miriam Harman, department director, called and said: “I saw you in the newsreel… Respect!”

Lately I was reminded of the conflictual attitude towards my work in the radio, when a certain series is callously censured while another wins the Kol Yisrael prize, especially on the Jewish-Arab issue. This is what happened later, too, when I worked for Israeli TV. On the one hand I was considered a rebel whose mouth should be shut, and on the other hand I was an inseparable part of the establishment, any establishment – be it high school, the Scouts movement, the army, and especially Israeli TV which I had joined when it was first created and where I worked for thirty years.

Miriam Harman was the first, but there were others too – Arnon Zuckerman, Yossi Godard, Amnon Ahi Naomi, Esther Sofer, Reuven Morgan and others whose names escape me now – people who supported me and enabled me to create, “for an establishment does not have to be monolithic”.

Do you think you could act the same way today?

Probably not. There were such times in the past, and there were others. I learned to survive. I used to say that when a large wave threatens to drown you, jump into it and wait for it to pass. Not everything went smoothly, of course, but I knew that one day the sea would calm down. I don’t know what it’s like today, perhaps the great deluge is already here.

And then you left for London to study film.

Tzipa and I reached London on the last day of 1966. Trafalgar Square was filled with celebrants. Some jumped into the cold pool. Others warmed up dancing alongside it. Freedom. Freedom. A day or two previously, we had screened the film

I Ahmad at the Hertzliya studios in Israel for the first time. Quite a few Jewish spectators dragged us through the mud. During the week after this experience at Trafalgar Square – the first week of 1967 – Tzipa and I were fascinated by the BBC. We were stunned at what we saw. As someone who had worked for a few years in Kol Yisrael, I believed that in spite of obvious limitations, I was living in a free country, and now suddenly, watching British TV, I understood what freedom really means. I thought: when television will finally begin to broadcast in Israel, this is what I shall try to do.

The choices you made, the issues you chose to work on in your films, usually deal with human rights, humanism, social justice – that’s where you are usually present.

Yes, a large part of my work dealt with these issues. But I also made many films about other subjects. Routine items for the Weekly Digest and programs on culture. I directed dramas and documentary films. I very much liked to follow processes in which a play becomes a theater piece.

What led you to create a film on torture at investigations in 1994?

Once in a while the press released items about torture methods applied by the GSS (Israel’s General Security Services), the police and the Israeli army. They sent a shiver down my spine, these descriptions reached us from the depths of the Middle Ages, as it were. We – at Israeli TV – hardly ever touched this issue. My suggestion to produce and direct a documentary film was rejected face on. But a few months later, Moti Kirschenbaum, then director of the Israeli Broadcasting Authority, called me up and gave me the green light to begin work on The Film that Wasn’t.

Could you describe the work process on this film?

Producer Liora Amir Barmatz joined me. We turned to the Israeli Committee Against Torture and other human rights organizations, and they had us meet ex-prisoners from the West Bank and Gaza. James Ron from Human Rights Watch joined us for the research and several days of shooting. It was important for me not to make do with just one case. I wished to get a general picture. Something that would prove or refute the possibility that physical torture is practiced in Israel as an accepted form of interrogation. We focused on over ten witnesses, each with his own story. Ron suggested we have a painter join the film crew who would draw the postures that the men described, as this was an accepted practice by various human rights organizations worldwide.

You felt that the testimony alone was not enough?

There were those who contested the legitimacy of the reconstructions. I did not agree. Television is not radio. I wanted concreteness. For things to be as clear as possible. I took care to check every testimony as much as I could. When I solid doubt arose – I gave up that testimony. I tried as much as I could to bypass the wall of mistrust that exists in every Jewish spectator hearing an Arab bear testimony. Especially if he speaks Arabic. Two interviewees did not speak Arabic. One of them was a physician from Ramallah, a urologist who spoke fluent English. He described being shoved into a tiny, very narrow cell that closed in on him on all sides, like a standing grave. He had to stand the whole time, there was a cold wind blowing from above. He had to urinate. He called the warden to open the door but the warden took his time. After he realized that they were trying to offend his dignity, he stopped holding back and peed in his pants. Compared to testimonies that described violent harassment – even death by torture – this testimony was somewhat marginal, but this doctor and his Oxford English opened a small crack, perhaps, in the Jewish spectators’ solid denial.

Another interviewee was a Jewish soldier, a Military Police interrogator who was filled with remorse for things he had done in his reserves duty. He was stationed in an interrogation room. When instructed by the interrogators, he would beat up people being interrogated with the club he held (‘strong blows’, ‘over one-hundred people being interrogated’). He was filmed with his face covered and his voice warped. He refused to say his name. In indirect checks I made, he appeared to be telling the truth. He said he refused because he feared revenge. Moti Kirschenbaum demanded I get the army’s response. I understood this demand but was against it. It was not easy. Moti was a friend, one of the Israeli TV’s most gifted people and one the more honest among us.

I said I would clearly announce at the beginning of the film that we bring words the way they were said, but we have no possibility of checking what exactly went on in the interrogation room. An announcement of an official body summing up an event might sound like a conclusive ruling. Still Moti demanded that I get the army’s reaction. The army refused. They suggested we remove the man’s testimony from the film. I refused. Naturally, I also refused to name him without his agreement. So, everything stopped.

The series was to contain two parts. The first dealt with interrogations on criminal charges inside Israel-proper, not security issues. The second part was supposed to deal with security issues. The two were planned to be aired one after the other, week after week, in order to check the assumption that what takes place in civil courts in the country is affected by procedures of military courts in the Occupied Territories.

After a several months’ freeze, the Broadcasting Authority decided to air only the first part, the non-security one. Half a year later, a compromise was reached that enabled airing the second part. A meeting was set of the military attorney and the said soldier. It was agreed that he would not be required to name himself. To my amazement, the fellow did not show up. From the attorney’s office I heard that “we told you so”. I felt betrayed, or dumb. How could I trust my intuitions. Perhaps the entire film was based on lies.

Then he called. Apologized. Something came up that kept him from coming or phoning. He asked for another meeting. I was sure the attorney would refuse. To my surprise, he agreed and the soldier showed up. Producer Liora Amir Barmatz and myself joined him at the military attorney’s office. The man answered all the questions and repeated what he had told me in the filmed interview. The military attorney did not make him say his name. The film was aired. It was called The Film that Wasn’t (1993/4).

How do you explain the fact that you could make such films for a public broadcasting service?

I want to think they believed in me. They knew me ever since my work at the radio. I received Israeli and international prizes. I was an employee of the system. The fact that you have Broadcasting Authority tenure is a great help.

The feature film Khirbet Khize, based on a story by S. Yizhar, would not have been made unless Arnon Zuckerman, Yitzhak Livni, Moti Kirschenbaum and Oded Kotler had fought to air it.

You felt protected, you couldn’t really be fired.

They almost managed it. They wished to fire me, of course, but there were always people inside the system – prominent among them was Arnon Zuckerman, Israeli TV’s director who defended my right to air my work. I remember finding out that the economic department of the Broadcasting Authority ran rumors that I was inserting single frames into my films with dissident messages, unnoticed because the film runs at the rate of 25 frames a second, single frames that affect one’s sub-conscious…

This sounds terrible. Other films of yours have also been censured. How do you feel in a workplace that censures you?

The censor, too, must make a living…

You spoke about your basic position which is skepticism, so this also enables a skeptical attitude toward your work.

I totally agree. I am certainly up for criticism. I know my truth. What grew at my family’s dinner table, what grew in me as a boy in the 1950s – excuse the triteness – were skepticism and humanism, not skepticism alone. I pose this question in another way, too. Say I was a German soldier, would I have had the strength to resist the Nazi regime in the name of the same values? I very much hope so, but am not sure.

When we asked you earlier how you came to make a film about torture in Israeli interrogation rooms, you described more of a procedure, and finally mentioned the Supreme Court’s ruling against torture. Why is it important for you to make these films?

There’s no need to present the idea that lies at the basis of my films every single time. In the past, when I made radio programs that dealt with the subject, I tried to dismiss my pretensions by giving naïve answers. If a sniper who is about to shoot a Palestinian child throwing stones in the West Bank remembers for a split second something he heard on the radio or a scene from a film I made that spoke to his heart, and unintentionally moves his rifle and points at the demonstrator’s leg rather than his head – then my work is done. That’s the maximum I can do.

Now, when you are no longer naïve, you say “that’s the maximum I can do”.

You add a small answer to this world that is filled with question marks. No more, but no less either.

Do you remember how the film was received? Was there any kind of public discussion afterwards?

As far as I remember, there were good critiques. But nothing essential happened. It is irritating. But that’s the way it is, that’s what you can do. A state is like a person, the main thing it knows how to do is to deny everything that poses a serious challenge. I can give you a more precise example, important, that minimizes everything I have done. Perhaps I’m exaggerating… Maybe not. Anyway, the matter I’m about to tell you now was brought to my knowledge during a military maneuver on reserves duty in 1970. I was not with my original unit. I was stationed there when I came back from abroad. We traveled in a truck back to our base in the center of the country, after having parachuted at night in the Jezreel Valley. The soldiers began to speak about something that apparently happened in the war of 1967. I heard laughter, mean laughter, the kind you hear when people talk among themselves about a secret event, perhaps criminal, something that they wouldn’t mention when an outsider’s ear is around their unit. The details were not that clear, but I realized it had to do with prisoners of war. I felt that something bad happened there, but didn’t really get what it was.

I was working for “Kla’im” [Heb. for ‘backstage’] at the time, a culture program on Israeli TV. I prepared an item on the play The Order produced by Hakameri Theatre, directed by Hi Kalus. The play takes place during the American Civil War. It deals with the treatment of prisoners of war at the time. I interviewed Binyamin Halevi, who had sat in judgment during the Kafr Qassem massacre trial, and coined the phrase: “An obviously illegal order, over which a black flag is raised”. When the interview was over, I told him what I had heard. He doubted it. “Such things cannot happen in our ranks” he said, but suggested I check and pass on the information to him.

A few months later I was called up again for reserves duty in the same unit. I interviewed two soldiers – separately, each without the other one knowing. One of them had followed orders, the other refused. The differences between the two versions were negligible. They both agreed that I pass on their information to the appropriate bodies in the army.

I informed Judge Halevi, who passed it on to the Investigative Military Police. Here is the crux of the matter:

On the sixth or fifth day of the Six Day War, the paratrooper unit landed at the airfield in Ras Sudar, a town in the south-western part of the Sinai, on the Suez Bay shore. The town was occupied with hardly any resistance. Thousands of Egyptian soldiers escaped from there to the nearby hills. Over 50 Egyptian soldiers were taken prisoner.

The paratroopers seated the prisoners on the ground in a closed place, a yard near a bakery, gave them water and some food. Several wounded men lying in a nearby building were treated by an Egyptian doctor. Talks developed between the prisoners and some Arabic-speaking paratroopers.

Some hours later, the paratroopers were ordered back north, and an armored corps unit arrived to replace them. The question arose what to do with the prisoners. The paratroopers said they would not let them on the flight, and the armored corps unit refused to guard them. So, the order was given.

The prisoners were all lined up in threes, stood with their backs to the soldiers, closed ranks, and all of them were shot. The armored corps men brought a bulldozer, it dug a big hole, threw the fifty bodies in and covered them with dirt.

One of the two soldiers I interviewed, an Arabic-speaker, said he had held a soul-searching talk with the Egyptian paymaster who asked him, among other things, whether the Israeli soldiers were about to kill them. The soldier said no. Then, upon receiving the order, he fired as they all did.

I was questioned by the Investigative Military Police. As far as I could understand, the two soldiers I had interviewed were also interrogated. A trial was held. The commander on the ground, whoever received the order from higher echelons and carried it out, was stripped of his rank. As far as I know, the commander who gave the order was not tried. Eventually he was appointed Chief of Staff. I was not tried, but was thrown out of the unit.

You told the story so they threw you out?

Yes. I suppose it was because I “badmouthed the unit”. The fact that an event of such magnitude did not raise a public outcry drives me mad to this day. For thirty years I have made many attempts to place the story on the public agenda. In vain. The censure, the fears of senior journalists to whom I turned – made it clear that my chances were nil. I decided to initiate a thriller series based on the event. The series was called Murder in Television House (2001), Batya Gur wrote its script, Asaf Amir was the producer, Asaf Tzipor was the script editor. It was aired on Israel’s Channel 2. The characters and events were partly imaginary, but the solution of the fictitious detective riddle is an almost exact replica of what I was told by the two soldiers.

Incidentally, while the script was being written, the common grave was unearthed at Ras Sudar, where the bodies of the Egyptian soldiers had been placed.

Aluf Ben, editor-in-chief of Haaretz, waged a long and exhausting battle to publicize the information. And indeed, on September 16, 2016, the following item was published in Haaretz under the heading: “Israeli soldiers murdered dozens of prisoners of war in one of Israel’s past wars: the affair was whitewashed and silenced”.

I expected an earthquake. None took place. I related this to the fact that what the censor had agreed to publicize was lacking in essential detail – which war, against which army, and why was there no specific mention of the killing of about fifty prisoners of war. On the other hand, using the expression “Israeli soldiers murdered” and having it approved by the army censor, sounded very bold. Nearly as bold as the expression “The massacre of prisoners of war”. There were no echoes to this story, as there were none for the series Murder in Television House.

Earlier you spoke of denial.

Right. The massacre remained unknown.

You said that the fact that you were not able to place the subject in the public agenda is common to all your films. This is rather extreme.

Yes. Perhaps I exaggerated.

When you make a film and wish to expose your Israeli spectators to a harsh picture of reality, do you use different directing strategies, search for another way to make your story accessible?

The creator’s classic role is to draw an emotional move like that of tension rising and descending and then rising again. On the other hand, there is the opposite dissident attempt – to expose processes, negate them and present their complexity.

The fact that you deal with controversial subjects, make dissident films to a certain extent, does that make you work harder as a director?

Not harder, but it does place greater responsibility. In his book Joseph and His Brothers, Thomas Mann crowns Naphtali, one of Joseph’s brothers in the Bible, as the forefather of journalists. He is like a “fast deer”, swift to close gaps of information among those far between. To stay sane. Our generation has this horrible fear and tries to keep the exclusivity of these things in the hands of economic, national, gender and racist elites.

When you deal with issues that express disruption, opposition or disintegration, do you plan the style, the expression of the film in advance?

I hope I deal with every film in its own way. The film somehow dictates its own language. Take the film about interrogations and torture, for example. As I told you, Moti Kirschenbaum, CEO of the Broadcasting Authority, demanded that I obtain the response of public spokespersons. After a loud argument I was forced to add captions. In hindsight, perhaps Moti was right. A state broadcasting service must accept responsibility for the things it airs. But the film became almost a collection of epitaphs, and the voice of an authoritative narrator laconically reading responses of the GSS, army or police – were not planned as the style of the film, and some people found this offensive.

I chose to begin and end with an emotional, harsh story of death during interrogation. Harsh but withheld. I see it as cinematic or dramatic thinking. You begin at a certain point and return to it after you have collected all your materials. This is one example of how reality changes the style of the film.

You move freely between feature and documentary. Which do you prefer?

The next film… The subject is the determining factor. Every time I make a documentary film, I ask myself why not turn it into a drama, and vice versa.

Still, how do you decide that this story will be a feature and that one a documentary, how do you make that choice?

I think about it in specific terms. I receive a story, or read a story, or as it happened with the play Crowned Head by Yaakov Shabtai. I see it and suddenly I know that what I need to do here is drama that speaks of today, no less than the last days of King David.

I am bravely filled with passion to direct the drama. Yankele is no longer around. He died nine years earlier. But, clearly, I am making a drama referring to our own reality.

Take for example the documentary film I made about the rehearsals of Nissim Aloni’s play The Gypsies of Jaffa (1971), whose other title is Just Don’t Think Twice. It contains many question marks and a lot of poetry, which I stole from Nissim… The film used cinematic language in order to learn what Nissim Aloni did in the language of theatre: splitting, partial transitions from one thing to another, observing techniques of the acting/playing person, as well as the richness of everyday life – not only the edges. Nissim’s theatre knows how to embody life’s sadness and difficulty as well as its battles, but mainly the richness of what it is to be alive. Meeting Nissim enabled me to dare. Nissim was an amazing person. I loved him dearly. I edited the film like a madman. Days I worked with editor Dalia Ezov, nights I worked alone. I knew it was an important film, the likes of which I will never have another chance to make. I was right.

On the evening it was aired on television I was doing reserves duty at the Al Arish airfield. I sat in the dining hall to watch the news when my film went on. The hall was full. At the end of the film, no one was there. I wrapped myself in a blanket and went out on guard duty. It was very cold. I thought it was all over. My dream of making films was smashed. The next day, I tried phoning home to speak with Tzipa, my wife, and for some reason the phone didn’t work. I tried to get used to the idea that I would finish my days as a junior economist at a government office. In the evening I spoke to Tzipa, and she said the phone had not stopped ringing. I understood that Jerusalem is not the military airfield at Al Arish. In hindsight, the film “Just Don’t Think Twice” that was made fifty years ago is still being aired today.

You made a similar attempt not long ago with the film Let’s Assume, for a Moment, That God Exists (2014), with moves that are half-fictitious, half-realistic.

I wished to throw off my prisoner’s uniform – imprisoned by rules, regulations, dilemmas, closed structure, planning – I wanted to be free. I ran into a reality made up of particles, things that happen by chance. Which create some kind of general picture as if not dictated by anything outside the moment. The moment dictates them. The moment of shooting, of editing, of thinking.

Where does the flock of sheep come from, entering the city?

A flock of sheep and goats lives in a hidden side of Napoleon Hill in Ramat Gan. At

7 a.m. the flock is taken out of its pen and disappears somewhere in this urban area. In the evening it returns to the pen. There used to be an Arab village there. In a certain scene, a goat stands on the edge of some cliff and looks. Its gaze leads the spectator to the continued journey of the flock and the shepherds into the Hebrew city. The past penetrates the present. I thought I should begin with that. I wanted to break some logical continuum, not to resort to familiar formulas. I try to do that once in a while in other films as well.

Who are the filmmakers who inspire your films?

Not necessarily in this order – Fellini, Mike Lee, Kubrick, Angelopoulos, Bergman, Antonioni, Ken Loach, Perlov. There are many others. They have all been my teachers. Especially those among them who show – or have shown – a love for mankind, a deep knowledge of cinematic language and a spark of rebellion.

Are you working on a new film these days?

Right now I’m shooting the rehearsals of a Nissim Aloni play – “Are there cockroaches in Israel?” Aloni began to direct it at Habima Theatre, but after a long rehearsal process, the theatre administration decided not to pursue the production and the play was put aside. Dori Parnes and Marat Parkhomovsky adapted the play anew, and these days rehearsals are taking place at Habima. As I told you earlier, fifty years ago I directed a documentary film that followed the rehearsals of The Gypsies of Jaffa, also by Nissim Aloni. Marat and Dori, who knew the film, suggested I close the circle and shoot the rehearsal process of Cockroaches, and ever since I’m having the time of my life.

Good luck!

Thank you very much.

Documentary Filmography / Ram Loevy

The Dead of Jaffa (2019), Dibukim (2017), Let’s Assume, for a Moment, That God Exists (2012), The Games They Play (2008-2010), Enter the Devil Drummer (2006-7), Barks (2002), Sakhnin, My Life (2005-6), May I Hug You (2004), Genifa, Genifa (2002), Close, Closed, Closure (2002), 14 Footnotes to a Garbage Mountain (Hiria) (2000), Letters in the Wind (2000), The Film that Wasn’t, series (1993-4), The Million Dollar Scan (1984), The End of the Bathing Season (1983), Between the River and the Sea (1983), The Buck Stops in Brazil (1982), Nebuchadnezzar in Caesarea (1980), Playing Devils, Playing Angels (1979), Voice of the Multitude (1978), Second Generation Poor (1976), Time Out (1975), Don’t Think Twice (1972), Israel in the ‘80s (1970-71), Barricades (1969-1972), I Ahmad (1966)