Translated from Hebrew by Aryeh Naftaly

It was obvious that for the issue devoted to the subject of "place" we'd want to talk to Amos Gitai. It seems like everything there is to say or write about Gitai has been already written or said. He's had a wide range of literature cover and analyze his work, he's given interviews covering every aspect of about his films and he's presented them in a variety of platforms. No other Israeli film director's work has been so closely related to questions of space and place and how they're presented, from his early documentary films through the fictional work he began doing in the 1990s. We met him a few days after he finished shooting another film, which also, unsurprisingly, attempts to illustrate a place through one long 90-minute shot. But we wanted to ask him about his beginnings, how he first got interested in "place" through documentary film.

How aware were you at first of the connection between the kind of filmmaking you aspire to do and the space or place in which it's filmed? We're talking about your short films from the '70s and your first work for Channel 1.

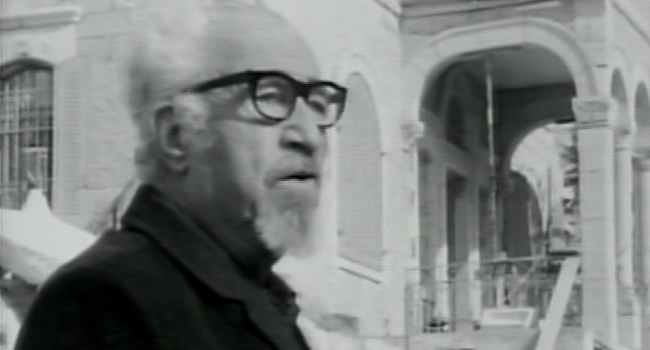

I think the fact that I came from architecture and didn't study at Sam Spiegel helped. I studied for nine years, first at the Technion and then in Berkeley, I did intellectual exercises about forms, structures, places. When I was in the architecture school at the Technion one of the most interesting teachers I met was Yitzhak Danziger. I'd call him one of my filmmaking teachers. He didn't always show up. Sometimes he'd be rebuked by the Technion; he didn't come to class when he didn't feel like it but when he did come he gave so much that it more than made up for his absences. And sometimes he'd take a group of students – I was his assistant at the time – and do exercises in observation with us. He'd take us out to a field just to look. Danziger is famous for his sculpture "Nimrod" but I think his works as an environmental architect and conceptual artist are very interesting. The work he did in Wadi Siach and the work he did in the renovation of the Nesher quarries in Haifa, and also the monument to the Egoz Corps of the IDF that he designed in the Golan Heights – an anti-monument monument since it deals with the individualization of bereavement and runs counter to all the concrete-and-iron monuments, instead creating a series of niches in the landscape. As far back as college I was attracted to craftsmanship and not design.

Tell us a little about those sessions with Danziger.

Danziger is very interesting since he understood the quality of contradiction. He himself was contradictory, including in his personal life, since he lived between houses and between places. No wonder his lover Rina Valero called the book about him that she published after his death "Place." But Danziger was a man of many places, not of one place only. When I was his assistant I had to look for him between his wife Sonya's house in Haifa, his lover Rina's house in Tel Aviv, and the place where he really liked to sleep, his mother's house, and I had to fish for him in one of those places. On one hand he went to demonstrations in Area 9 against the expropriation of land in Sachnin – he was political – and on the other hand he made the statue of Jabotinsky in Metzudat Ze'ev. So he was a contradictory type, and he embodied many of the contradictions connected with this complicated place. I think he was interesting. He wasn't a purist, he wasn't politically correct. The territory known as Israel, with all of its contradictions, was the raw material within which he worked.

I could add that he was a local but not a provincial, and that's a big contradiction in itself, how to do things that are connected with the place while still belonging to a broader world and not to be provincial or nationalistic or to make a fetish of the place.

Later, when I was in Berkeley, I worked with an architect named Christoph Alexander who did vernacular architecture, architecture which is a product of the communities that create it. That whole nine-year period in which I studied a profession that I didn't end up working in was a wonderful period and I'm grateful for it. Later, when I made the film Ananas (1984), I was influenced by what I'd experienced at Berkeley in my doctorate studies – courses in economics, in Marxist philosophies that deal with third world economies. I think that when you direct a film you don't have to shove everything you know into it. It's better not to force it. But you should certainly be an educated, broadminded, cultured person who understands the context in which you're working. Those nine years, which really is a long time, were my preparation for the understanding of context. Now I can talk about many, many things and I feel like I know what I'm saying because I studied them.

What was your doctorate thesis about?

Yes, I have a PhD. You should call me Dr. Amos Gitai.

My thesis was about something called "community theory." I took five Jewish communities and studied their architectural development. I claimed that the Jews had a different strategy than the cities in which they lived. On one hand they accepted the architectural style of the societies in which they lived, and on the other hand they did things differently. I started with Sana'a in Yemen. According to records of the Jewish Quarter of Sana'a the Jewish residents had a problem; since they had to build according to the Pact of Umar which states that all the houses of non-believers, i.e. Christians and Jews, have to be one storey lower than those of their Muslim neighbors, what could they do when their population grew? So they built trenches. They simply built vertically, but in the opposite direction, downwards. There's an entire system of tunnels in the Jewish Quarter. On the holiday of Sukkot they'd build a little Sukkah [temporary dwelling] on the roof, and if their Muslim neighbors didn't make a fuss about them they'd gradually expand. I got this information from photographs and sketches, some by Goiten, an expert in Middle East affairs who lived in Jerusalem in the '30s. This illustrated to me the great interest in space prevalent in the '30s, which was a result of the influence of Magnes and the Jewish-Palestinian Peace Alliance among other things. Unfortunately that tapered off when I was in the Technion. In Venice the Jews had the opposite problem: From the 16th century on they were forbidden to own land so they wouldn't "taint the soil." In 1516 the first ghetto in the world was established in Venice and the Jews had no choice; when they wanted to expand they built the first skyscrapers in Europe – the opposite of Sana'a. These things always attracted me. I remember leading a strike of the architecture students against the history studies at the Technion because they didn't really teach history, they only taught about Rome and then the European schools, Bauhaus etc. But they didn't try to teach anything else, not even Muslim Spain. Not even the Middle East, nothing. But that's a different subject.

When did you realize you didn't want to do architecture any more and turned to cinema?

In the Yom Kippur War I had a Super-8 camera that I filmed with. That camera was a big help to me psychologically since it served as a partition, a sort of defense. Other people who were with me in the helicopter that crashed were either killed or went crazy. The cinematic act I had to perform protected me. Later, when I studied architecture at the Technion and some of the courses were boring, sometimes I'd submit a film instead of a paper. My greatest achievement at the time was when I submitted a film to my math teacher instead of a final exam. I made a sort of primitive animated film and submitted it to him. Later I directed films for Israel Television and the first film Israel Television let me direct was a 20-minute film on things that I see from my mother's window. That was all. Just try and convince some channel to let you do that kind of project now, but it was aired on Channel 1.

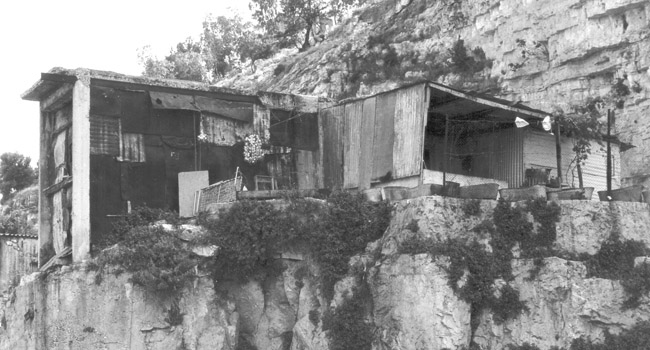

In '76 I filmed Wadi Rushmiyye for "Second Look" [a news program]. I was interested in people who build themselves shelters, autonomic spaces, by recycling all sorts of materials from the city.

Why did you quit architecture?

One reason I quit architecture was that I think that architecture today is concerned with the fabrication of design. That is, the architect makes a sketch in his office and that's that, there's no interpretive process. The worker or the contractor or the craftsman has no impact on it – on the contrary, if he deviates, he's fined for the deviation. And I think that's a mistake. This is a continuation of the works that I studied for my doctorate which demonstrate the personal input of the craftsman. For instance, every craftsman in Sana'a did the stained glass slightly differently. And in the film Wadi (1981), Miriam, one of the protagonists, can plant her tree slightly differently. That's the difference between filmmaking based on very strict formats and filmmaking that preserves the element of craftsmanship. Now I think filmmaking is in the same danger that architecture is already in – it's been totally ironed out. And under the pressure of money, of broadcasting entities and so on, they want everything to be pre-simulated and fabricated. Therefore the word "planning" requires clarification. I still think it's good to plan, but the fabrication process is an interpretive process. It isn't a process of fabrication without rethinking.

So you arrived at your style through dealing with space intellectually.

You can't make a progressive film in a reactionary manner. That is, the form is an element of the statement. A film is a complete personality that should make a statement. Making films that don't say anything is problematic, but you can't instrumentalize form in order to make a statement. The documentary trilogies Wadi and Bayit, and you could say Field Diary as well, all indicate names of territories and talk about the fact that the arena is a space. And if there's space for a conflict, then there's space for a solution, a meeting-place.

When you approached Bayit, the first of the trilogy, did you realize its potential as an analogy of the conflict when you began?

I didn't approach it with set political statements which I then applied to the film. I think Bayit (1980) politicized me, which I think is the right way to go about it, i.e., expose yourself to the material, to its contradictions, to its characters, and let that be your guide. The brutal attacks on the film and everything that happened afterwards forced me to decide to either back off and say that I'm just an architect who made a film and it's no big deal, or to defend it, which meant exposing myself to attacks, having people say all sorts of things about me. I chose the latter, and that was the end of architecture for me. In that sense, Bayit was a significant film for me.

Did you know from the beginning that you were making a politically controversial film?

No, at first I thought of doing a completely different story. I wanted to do a film about a group of people who work next to a machine, and the repetitive motion of the machine determines their biographies. A textile machine or something of the kind. Then I changed my mind and tended more toward the concept of home. It often happens that there's a synchronization between macro processes much bigger than me and my development as a filmmaker. Remember, in the meantime Israel Television was taken over by the Likud government and Menachem Begin appointed Tommy Lapid director general of the Broadcast Authority, and the project, which would have been accepted by pre-Tommy Lapid Israel Television, came up against that change. I knew I was touching a raw nerve but I never imagined the degree of manipulation and malice they'd use. My mother told me at the time: When you take a pill there's an element of poison in it, the question is how much. But it can also heal you. And that led me to different places.

In the two trilogies, Wadi and Bayit, you avoided "place" for years.

In Wadi, once they build the Great Mall (in the third film), that means they want to be a Great Mall. They want to be America. So I, as a documentary filmmaker proper, albeit non-self-declared, document the process that the place undergoes, of losing its identity. Actually, in doing so I'm doing nothing more than documentation since the statement only comes from what the film itself says. By the way, there's nothing there any more because they turned it into freeways. So if I were to make a fourth film, which I don't think I'll do, there's nothing there to document, it's all been destroyed. The same is true of Bayit. The house was totally demolished, the characters have scattered to the four winds, and I can only address the diaspora. I didn't want to address only the Israeli diaspora or the Jewish diaspora so I went to see the Palestinian diaspora in Amman and other places. You could say that the film Free Zone (2005) lies on the same geographical axis as the third film in the Bayit trilogy. It basically says that maybe the only way the conflict of the region we live can be solved is through its destruction. We're living in a big contradiction. Whenever we talk about place, we're also talking about holy places, temples, we're talking about beauty. In all these senses, including the term "beauty," each side has a precise interpretation of what beauty is, what it considers sacred. Maybe conciliation can only come through the annihilation of all these concepts, for it all to be one big parking lot for American cars.

By the way, it could also be said that Field Diary (1982) documents the process of the nullification of a place, in the name of the love of the holy place. The bulldozers and the ugly houses and the insensitivity to such a delicate landscape. That's why I use a lot of traveling shots, because the film deals with the nullification of a place.

How did your cinematic language develop?

For the first Wadi I had a cameraman named Yossi Wein who agreed to shoot the film even though he mainly did feature films, and he always used to tell me: "Amos, do you really want me just to set up the camera and not move it?" No, you don't have to move it. I felt very free. I hadn't studied filmmaking and I wouldn't even call myself a cinephile. I didn't watch many movies. But I think my main esthetic influence was my father, Munio Gitai-Weinraub. He was one of those architects who are really very anti-architectural as we understand architecture today. I mean, when we think of Bauhaus today, we think of design. The approach of architects like my father, who were raised on Bauhaus, was that architecture should be practical. After all, one of the problems with Bauhaus after the war was the way it was understood, since it was a very interesting synthesis of political notions and esthetic notions. But after the war these things were divided. East Germany only took the political elements and even rationalized kitschy Stalinist architecture, while West Germany only took the esthetic elements. They basically split Bauhaus. Ever since East Germany was defeated, Bauhaus has only dealt with the esthetic elements. But the interesting thing about Bauhaus is the synthesis of sociopolitical elements: questions of housing, industrialization, design. The current Bauhaus historians, and I've had big arguments with them, declared victory, so okay, they really did win. But when my father, as a refugee from Switzerland, had to decide whether to take a boat to New York or come to Palestine, he decided not to go to New York because he was interested in the societal element, he thought it was stronger here, because of the kibbutzim and so on. Now the sociopolitical element has evaporated and all that's left is the esthetic.

The debate surrounding the practical side of planning had a powerful influence on me, I can say that now. My father was an esthetician and was very visual in everything he did. His mother, my grandmother, was an esthetic person too. He designed her house in Kiryat Bialik. She wanted it to have a heavy steel woodstove like in Germany to use for heating and cooking as well. So he got her a woodstove. And I remember watching her make the fire, how she put in the newspaper with the ashes inside and the whole ritual, her choreography, and it was fascinating. They all came from a simple, precise esthetic and I think these things influenced my cinematic approach.

When and how did you begin to experiment with sequence shots?

Before Field Diary I shot a film in the US, American Mythologies. It isn't very well known in Israel. And there I started working on the sequence shot as a documentary element, this was in 1979-80, I filmed hitchhikers on freeways. And I remember when I started working on Field Diary with Nurith Aviv, the cinematographer, I showed her the shot and told her I wanted the whole film to be shot that way. I told her we'd take the car every day, drive from Tel Aviv to Nablus, from Nablus to Ramallah or Bethlehem, then to Jerusalem and back. We'd do that every day and we'd see the most banal things – two soldiers standing by a wall, one of whom says the Arabs should be wiped out, or a group of soldiers in a field, that's what we'd film. And later, interspersed with that, were more planned-out elements such as the first scene – Bassam Shakra's house. Then came the question of editing: does the editing have to follow the territorial continuity, the chronological continuity or the thematic continuity? I didn't want to follow any of the three, I thought we should find an organic continuity that isn't dictated by them. So we started shooting, this was in the Spring of '82. Developments came into the film such as the Bar Kochba burial ceremony which I intuitively knew was so surreal that I had to be there. I find processes of recycling ancient history into modern politics fascinating. I asked at the Government Press Office in Jerusalem if I could be invited to the event and they said no, that Menachem Begin wanted it to be a private event and only a few journalists would be invited who would be flown by helicopter to cliffs in the Judean Desert, and I wasn't invited. So I took the cameraman from Israel Television who shot Bayit for me, Emanuel Aldema, and told him I wanted to film the scene because if he came along, with all the confusion that always happens at this kind of event, they'd think he was filming for Israel Television and nobody would ask questions. And so it was, we filmed it. I filmed the parts that happened in Lebanon because they didn't let Nurith cross the border; they said that women weren't allowed into Lebanon. So Razi Bukai, who was the assistant cameraman, came with me and we drove into Beirut together. In a director's work there's an element of strategy which I needed in order to safeguard my freedom of action as a director. The same was true of Field Diary and Ananas as well as Bangkok Bahrain (1984).

When did you decide to go into feature films, and did that decision lead you to stop making documentaries?

I went to Bangkok with Edgar Tannenbaum and Roni Katzenelson in 1984 to film Bangkok Bahrain, and what I saw shook me up so badly – a prison for 12-year-old girls and the city's sex industry – that I didn't want to do documentaries any more after that. It was absolutely shocking. I stopped for a few years, I filmed Esther (1986), then Berlin and Jerusalem (1989), then I did a film with the Eurythmics (Brand New Day), and only in 1991 did I go back to the second Wadi and Bayit. I think, on theoretical level, making documentary cinema is more complicated than making feature films. At a certain point I felt that my dialogue with the place – place in the sense of Israel or Israeli society – was limited because I don't think most people are interested in the things I'm interested in, so I can't obsessively insist on talking to them about things they aren't interested in. I place my films before them, I'm glad you write about them, that there are people who like them, but I can't spend all my time dealing with the implications. I think documentary cinema demands many things that feature filmmaking doesn't demand. It demands much more precise ethical obligations of the director vis-à-vis his subject. I couldn't make The Promised Land as a documentary because I didn't want to expose those people to what it's saying, which is why I chose to make a feature film in which the women in it are actresses who've agreed to be filmed. Documentary cinema has to be much more strict. I'm also against docu-drama. I don't like it. But the political reality might create situations that draw me into making documentary cinema, it's possible. It's getting to be that way.

As we mentioned, Gitai's next film is coming out soon, and it's based on a story that Gitai read in a newspaper. But plenty will surely be written about it in detail when it comes to the screen.

- My Mother at the Seashore – 1973. Bayit (1981). Yoman Sadeh (1982). "Bangkok-Bahrein" (1983). Ananas (1984). Esther (1986). Berlin-Jerusalem (1989). Birth of a Golem (1991). Golem, the Spirit of the Exile (1992). Zirat Ha'Rezach (1996). A House in Jerusalem (1998). Zion, Auto-Emancipation (1998)/ Yom Yom (1998). Kadosh (1999). Kippur (2000). Eden (2001). Kedma (2002). Alila (2003). Promised Land (2004). Free Zone (2005). Disengagement (2007). One day you'll understand (2008). Carmel (2009). The War of the Sons of Light Against the Sons of Darkness (2009). Roses à crédit (2010). Lullaby to My Father (2012). Ana Arabia (2013). Tsili (2014).Rabin, the Last Day (2015