Anat Even and Ran Tal

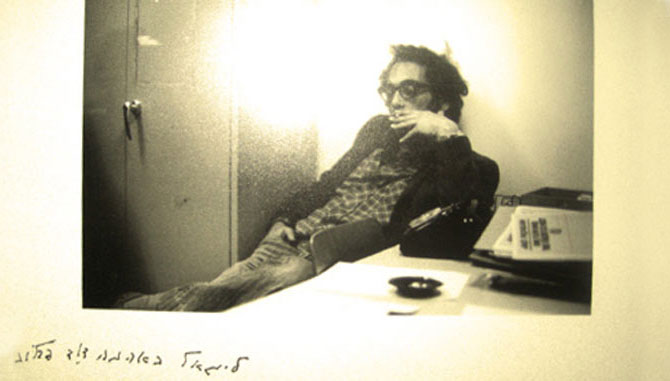

Deciding whom to interview for the first edition of Takriv was very simple. It seems that no one here is involved in so many different aspects of film making: Yigal Bursztyn is a prolific director, a revered lecturer of cinema, an astute critic and an expressive writer. Interestingly, when working in any one of these capacities, the others come into play too. As a director he is always inclined to theoretical discussion. When he writes books and reviews, you can't help feeling his passion and desire to check it out through his own camera.

Bursztyn’s work isn't simple. His writings conduct intricate discourse with novelists, poets, philosophers and artists. In his films, he challenges language and format, conducts experiments full of zeal and humor. His love for cinema and his polymath knowledge turn every conversation with him into an adventurous voyage whose starting point is known but not its end.

His last wonderful book Intimate Gazes (Mabatey Kirva, Magnes Press 2009), which was published last year and won the Bahat Prize, was hardly a necessary excuse for us to set up a meeting in his Tel Aviv apartment.

Let's start at the end, with Intimate Gazes. What drove you to write it?

I am sorry to disappoint. I usually write about movies when I'm not making one, an occupational therapy of sorts. Intimate Gazes started when I finished filming The Guide for the Perplexed (More Nevochim, 2006). I planned to go to the Knesset and film the ceremony commemorating the 800th year to Maimonides' departing. In festive ceremonies, especially held in pompous venues like our parliament, funny things that I like always happen. But instead of attending the ceremony I ended up in hospital – heart attack. Surgery paralyzed me for a few moths, and I wanted to use this time to work on some booklets I had written for the Ministry of Education. I was never quite pleased with them because they were informative and didactic. I was hoping to turn them into a book that would be wilder and unhindered. I am all for wild and unhindered writing. I thought it would take two weeks. It took two years, at least, and would probably have taken a few more if I hadn't been browsing, looking for various data, through the two volumes of the Cinema, by Gilles Deleuze – a wild and unhindered, complicated and irritating French writer. I had tried reading him a few times before, and gave up every time. It was beyond my understanding. But this time, reading Cinema 1 and Cinema 2 as reference for writing, using the index, rather than from the beginning by the chapters order, trying to understand – I realized Deleuze charges the reader with the burden of understanding. I found it flattering and challenging. From this realization I reached another: Deleuze was addressing the same subject I was: thoughts about films, how films think and how their thinking or lack thereof affects the viewers' thinking or lack thereof. I suddenly found an ally.

Reading a book through its index is an interesting method. But you are avoiding the question about the relation between writing and doing. You could do all sorts of things, but you write, and seriously.

What do yo mean “seriously”?

You are committed to writing. You have a need to do it, besides filming.

I would definitely write less if I were making more movies. When you fall in love with a girl, you write her letters. When you're living with her, you don't have to write anymore. It is true though that in both situations there is passion. Perhaps even more in the former. Maybe this is the “seriousness” you are referring to?

Does your writing feed your film-making? Is there mutual insemination between writing and making films?

I doubt it. My writing about cinema mostly feeds my film-making by compelling me to view films responsibly, with concentration. You can watch movies without writing about them. The trouble is I am not a very responsible viewer. I have this tendency – which is a plight for a person who writes about cinema and can be a boon for film makers – to impose myself on other people's films, to appropriate them, make them my own, to see what I want to see in them and not to see what doesn't interest me. In that sense, writing disciplines my viewing. But this urge to barge in is so strong that it can sometimes overcome the writers' responsibility. One of my colleagues in the university informed me, not without gloat, that a close-up of hands milking a cow's tit in Sallah Shabati by Kishon that I described in The Face as a Battlefiled (Hakibbutz Hameuhad 1990), does not exist in the movie. She was right of course, the scene shot by Kishon only shows Gila Almagor and Shaike Levi's faces while milking the cow, but this is what I remembered from this loving encounter between the two. I once read the poet Wislawa Szymborska's memoirs. She describes there a scene from a Bunuel film without mentioning the film by name. I think she meant That Obscure Object of Desire: Fernando Rey walks on the street and passes by a toothless old woman embroidering on a floor rag dripping with murky water a silk lily, the emblem of the French throne,. One day I saw this film on TV – no old woman, no floor rag, and no embroidery at all. It's just Fernando Rey passing by a young woman donning a white wedding shawl on her shoulders. Loving Bunuel, Szymborska imagined the film to be more Bunuel than Buneul himself made it, adding this wonderful scene, which was never there. I, not loving Kishon, added this vulgar scene, a figment of my imagination. I later changed my mind about Sallah Shabati. Today, if I could apologies to Kishon I surely would.

To the matter at hand, it could be that watching Bunuel enriched Szymborska's poetry, just as my watching Kishon might have honed my cinematic skills. But I doubt Szymborska's writing about Bunuel affected her poems in any way, just as I doubt my writing about Kishon affected my films in any way. One should realize that watching movies is very different from philosophizing about them, or from cinema theory if you will. I don't believe cinematic theory has any effect on the movies industry.

Could you elaborate?

I think sometimes watching films is confused with film theory. This happens a lot at universities and schools. Just like reading books, viewing artworks, listening to music and perhaps reading philosophy, watching films is essential for making films. But all of these, barring the philosophy texts perhaps, are not theory, certainly not cinematic theory. They say the word theory comes from the Greek word for observing. However, not an observation that seeks to experience the observed, but one that aims to explain the contexts around it, its meaning, and tries to draw conclusions from it. It is a framework of assumptions and conjectures that abides by logical principles and systematic thinking. Assumptions and conjectures are for the medium of writing. This is why cinema theory, more than viewing and discussing films, is viewing and discussing texts about films. It tries to link cinema and philosophy, art, psychoanalysis, ideology, linguistics, social application and so forth. It seems to me that creative filmmakers should make those links themselves. If they are made in their name and on their behalf, then what is the point? Theory books will be of no use for people who don't use their brain, let alone those who don't use their intuition. No theory can serve as substitute for them.

Looking at it another way, you could say about theory that it is largely rational while art is largely emotional. The word largely is important here, since there are, of course, theories expressed emotionally (Plato, Pascal, Niche, Eisenstein, Bazin), just as there is art that is also rational (Dreyer, Eisenstein, Chris Marker, Godard). In these cases, theory is also art and art becomes theory; the distinction is blurred. These are inspired moments both for theory and for art. They prove that theory can be poetic in its way.

In this eternal deliberation about the link between theory and practice, people always use the example of Eisenstein's montage theory, which changed the face of cinema, and Andre Bazin, as the instigator of the new wave. People forget that Eisenstein's theory was preceded by Strike, without which and without Battleship Potemkin and October, his theory might not have been formulated. It is true that prominent figures of The New Wave such as Truffaut, Godard, Resnais, Marker, Rouch and Chabrol, gathered around Bazin and were inspired by him. His wonderful essays established his authority and elicited profound admiration among creators. But if you examine their works, Shoot the Pianist, Breathless, Last Year at Marienbad, La Jetée, Chronicle of a Summer and Le Bonnes Femmes, fiction, documentary and experimental films, they are the antithesis of the “realistic objectivity” that Bazin promulgated. It's not that the New Wave filmmakers rebelled against Bazin – they rebelled against the films and the film industry of his time.

On the other hand, it seems obvious to me that movies influence theory and provide materials for it. Making films surely inseminated my writing too. First and foremost, film making instilled in me the confidence, never mind if justly or not, that I understand what I am writing about, and it gives me the courage to speculate about how things have been made or filmed. In Intimate Gazes I speculate that the Lumiere brothers instructed the workers walking out of the factory not to look at the camera and not to go near it. I might be wrong. As far as I know there is no account of how the film was made, but I feel that without any directive instructions Employees Leaving the Lumière Factory would not look the way it does. And the speed at which the workers are leaving the factory— you can see they are really hurrying— allows the scene to last exactly 50 seconds from the opening of the gate to its closing, which was the time capacity of one reel in those days. Could this correlation between the film duration and the celluloid length be incidental? And how come the workers aren't looking at the camera? If it weren’t for the awareness of gazes I had acquired while making documentaries in the 70's, when looking at the camera was considered taboo, and if it if weren’t for the awareness of timing that comes with experience, I wouldn't have noticed these details about Lumiere’s movies, and I wouldn't dare criticize the accepted view about “innocent” and “primitive” films, that they were made by the forefathers of cinema presumably without awareness of what they were doing.

Do you outline this hierarchy because you ascribe less importance to writing about cinema than to producing it?

A film creates a world. Writing about it merely interprets it. This is a subjective feeling, of course. The question is what is meant by importance. If you mean influential, I am convinced that films influence film making more than writing about films. Talking and writing are mostly important in drawing attention to films, bringing audiences and money to the filmmaking industry.

Of course, regardless of the medium now, good writing like good cinematography broadens the reader’s or the viewers' horizons and challenges his or her intelligence. In that sense you probably can't quantify the influence of writing on the minds of readers or viewers in comparison to the influence of a film. So any ranking is pointless too. I don't dismiss theory as such or its impact on readers. At its best, it can touch and provoke feeling just like literature or poetry or any work of art or thought. Such are the writings of Eisenstein, Bazin and Deleuze, and now Lev Manovich and Paul Virilio. However, theory affects theory, affects readers, thinking, culture, whatever you may think of, but it doesn't affect movies! Perhaps in some indirect socio-historic way, but certainly not directly.

Let's talk about your films. There is always something grotesque about the characters, a kind of persistent non-realism engendered differently every time. You consistently try to avoid the real dimension and reach other places, especially in fiction films. Why?

I probably don't like the real dimension, reality, too much. The trouble is that reality is like a spat-out wad of chewing gum; it sticks to your shoe and when you try to take it off by rubbing it with the other shoe, it sticks to the other one too… I am not talking about the wonderful reality of nature, trees, ocean, birds, women, men, sunsets and sunrises, I am talking about social and political reality created by man.

It seems you want to make your characters cross some line. Or maybe transit between different historic periods? You do that in most of your films.

Maybe, in a sort of Quixotean manner, I do it to escape the present and connect to the past, to what I love about the past. Perhaps, to be embraced by ancient wisdom? This yearning is not only present in fiction films, but also in documentaries I make or want to make. In The Guide for the Perplexed, I asked to include scenes in which two actors, playing Maimonides and the Arab philosopher Averroes, sit in a Tel-Aviv café, watch the street and make remarks in Arabic out of the 850-year-old texts. They lived around the same time, suffered the same religious persecution, and we know from Maimonides' own writings that he considered Averroes a great interpreter of Aristotle. Even if they never actually met, why not bring them together in a film? Isn't that what cinema is for? In my view these are two cosmopolitan sages linked by philosophical wisdom. Generally, I would say that any wise person is a cosmopolitan, to the irritation of religion mongers and politicians. A few days ago in the press, Prime Minister Netanyahu was quoted was quoted as saying, in regards to the deportation of 400 foreign workers' children, “We face a dilemma between humane values and Zionist ones”. Maimonides and Averroes see no dilemma. For them both a clergyman of deep faith and the political leader of a community can respect and uphold universal values.

Anyway, since not a single foundation for culture or cinema agreed to invest in Guide to The Perplexed, I had to make do with a very tight budget, $70,000, for an hour-long picture filmed in three continents. We had to relinquish the expensive acted scenes. I really don't know whether what deterred investors was the topic – maybe the Maimonides scene – or my approach to it— seemed esoteric to them. Either way, they would not invest. That's reality. Another excellent reason not like it!

Still, in defense of reality, you could say that when it is bad, it can be an excellent source of inspiration for a good film – as a starting point, as motivation, not necessarily as a document or record. I mean, I don't think films emulating reality are interesting. It is interesting when they create a new, alternative reality that compels a person to think about the actual, already familiar one.

Could you elaborate, especially in the context of documentary cinema?

Oscar Wilde once defined the difference between journalism and literature: “Journalism is unreadable, and literature is not read.” To me a documentary – “creative treatment of true reality—” according to John Grierson's classic definition – is a form of literature, just like fictional cinema. A “creative treatment” leads you beyond mere documentation or information. The latter requires non-intervention, objectivity. It's not that journalism, reportages or “objective” documentaries are necessarily uninteresting, but rather that they are only as interesting as their subject is. Almost any film and report about the Lebanon War would be “interesting” to watch if the Lebanon War interests us. But Border by Michal Rovner (1997), with the blurry images, the double exposures, the associative narrative, the elusive characters, the clash between soundtrack and visuals, is not only interesting but also challenging, like the stylish animation in Folman's Waltz with Bashir, or the arbitrary density of filming inside a tank in Shmulik Maoz's Lebanon. The transcription of reality, which for years television editors considered ideal, is entirely dependent on reality, on accepting it as self-explanatory and ultimately on reconciling with and reaffirming it. But if you treat reality “creatively,” in compliance with Grierson's decree, rather than just “documenting” it, you create something new that's more than just a replication. And then the film is interesting not only because of what it says, but also, and perhaps primarily, because of how it says it. And if reality is told differently, presented differently, then maybe it will be regarded differently. Naturally it is hard for us to change the way we think, and so, back to Oscar Wilde, many opt for the easy route: replicating and documenting – making journalism; and few opt for challenge and creativity in documentary cinema – writing literature. For me, documentary cinema, when at its best, is a genre in literature. If you find the word literature confusing, you can replace it with the overused romantic word art.

Are your films self-aware?

I wonder. A distinction should be made between me and my films. The films have lives of their own, and I can't attest to them any more than you can. As for myself, unlike my films, I try not to be too aware of what I am doing. Being so could be handicapping. Nabokov once said, “Writers are doomed if they become aware of what art is and what the duties of an artist are.” It relates to what we talked about before, the connection between theory and practice.

By “aware,” I mean that obviously you are aware of the cinematic workings, of the fact that, since The New Wave cinema, cinema is text, a subject matter for discourse, and you are part of that discourse.

I don't know that I am less or more aware of the cinematic workings than any other filmmaker, if you are referring to the so-called “language” or “cinematic syntax”. My films, at least some of them, consciously play with ideas, which might make them seem “theoretical”, but cinematic workings, even if inspired by ideas, take place in concrete reality with concrete characters, cinematography, lighting, editing – of which any filmmaker is aware. The obsessive engagement, which may be typical of my films, or of most of them, with the discord between ideas and reality, between ideas and ideologies, versus pissing, belching, desire, breathing, probably stems from my biography, from the idealistic upbringing, verging on brain washing, in which my generation was indoctrinated in the 1950's. In the movie about Maimonides, a girl has her picture taken while sitting on the lap of the Maimonides statue. I am all for a giggling girl sitting on the lap of a profound and refined idea. I find this contrast charming.

How do you decide whether a film should be documentary or fictional?

I find the distinction irrelevant. Letters to Felice (Michtavim le Felitzia, 1993), which seems documentary – a record of one Sabbath eve in a cafe in BatYam— is “fictional” just as much as Everlasting Joy (Osher lelo Gvul, 1996) – a motion picture with actors and story lines that I directed around the same time. The people in “Letters” played themselves, and during rehearsals they and I composed their stories, which appear to have been captured at random. Every character or a group of characters in this Bat-Yam bar built a very simple, basic story: a sad woman gradually cheers up and ends up dancing with the singer; an elderly woman looks for a mate and ends up flirting with an adolescent boy; two bullies drive off a friend of one of the girls to stay alone with her… you can't film this kind of situation if its not under your control. Nobody would be willing for you to invade their intimate moments just like that.

Large segments of Leibowitz in Maalot (Leibowitz in Maalot, 1980) are directed reconstructions in which people play themselves. All the preparations in the town for the visit of the three thinkers— Yeshayahu Leibowitz, Israel Eldad and Menachem Brinker— for a panel debate about a “crisis of Zionism” were filmed months after the event. Following the dailies that recorded the questions asked by people at the “real” debate and “documented” on film, we returned to Maalot, located the people and reenacted along with them the events of the debate day. We directed them a month or two after the event, we took them back to what they were doing that day. Not to mention the provokers we brought to the debate itself, who sat in the audience and asked questions that upset other listeners and the debaters. The ride and the seemingly spontaneous conversation in the car driving the three philosophers was carefully planned, modeled after previous rides Leibowitz took with Eldad and Brinker. Brinker, who helped me plan the film, was in fact an under-cover agent working for the production: asking questions, stimulating the conversation as if the crew and I weren't there. He sharpened the confrontation between Leibowitz and Eldad, which was spontaneous, but occurred numerous times before we made this film. If this spontaneity had not been planned and controlled, it probably wouldn't have transpired at all. Documentary films don't just happen, they are directed. Nisim Aloni used to say that whenever he knows he is being filmed, he becomes an actor. A documentary director would have had to direct him to look and act like Nisim Aloni and not like an actor impersonating him.

For me, a documentary film is a film that proclaims itself as documentary and emanates documentary credibility. It doesn't matter how it was made, whether documented in real time or reconstructed, whether the characters in it are acting or have been “caught” in natural action, or whether they were “directed” or “utilized” preplanned mise-en-scenes. A fiction film is a motion picture telling a story that proclaims itself to be a story, a fictitious tale, whose characters represent people who don't exist. Some films are in between, like Abbas Kiarostami's Close-Up (1990) and The Legend of Nicolai (Ha'agada Al Nicolai Ve'chok Ha'shvut, 2008) by David Ofek; these are constructed as stories and combining the genres, where non-actors are utilized as actors in planned mise-en-scenes that nonetheless purport to be documentation or reconstruction of real events. It is confusing for those who ascribe importance to genres. Listed as fiction, HaMadrich LaMahapecha by Doron Tsabari and Ori Inbar fomented unrest in the Israel Film Academy awards this year,. But it has a story doesn't it? Like most documentaries.

Just as most documentaries have a fictional or story-like aspect, there's a documentary aspect to fictional films. They document sites, actors and above all the zeitgeist. What is documentary and what is fiction in my Everlasting Joy, which is proclaimed fiction but follows the biography of Spinoza just like any historic documentary with narration and everything? There, Ariel Zilber, who plays the Dutch Jewish 17th century philosopher Baruch Spinoza, hugs Yael Almog in a Tel-Aviv street while quoting real Spinoza texts out of The Ethics, and then sings Spinoza texts to tunes he had composed for the purpose of this film? The idea to sing passages from Spinoza was Ariel's — very much his own invention and improvisation. Everlasting Joy, among other things, is a documentation of the singer and composer Ariel Zilber, just like any movie documents its actors.

Genres have been intermingling almost since the very beginning of cinema. In 1902, Georges Méliès “documented” in his Paris studio the coronation of Eduard the 7th, which took place weeks later at Westminster Abbey in London. This pre-construction allowed Melies to show the coronation on the day it took place, and audiences flocked to see it on screen. But even if The Coronation of Eduard VII is fiction to us, it is undoubtedly an accurate documentation of how the coronation of the king of England was imagined in 1902. On the other hand, a fictional film like Bicycle Thieves, based on a fictional novel – whose story is tight and flawlessly composed, like a Hollywood movie, though most of its actors play themselves in real locations that show genuine poverty – is a highly accurate documentation of the hardships afflicting Italy after the Second World War. I think it was Godard who identified Melies as the first documentarian, and the Lumiere brothers as the forefathers of fiction. If my speculations about the way Employees Leaving the Lumiere Factory is right, then he certainly got it right.

You refer to your fictional films as documentaries and vice versa. This is one of the interesting things about your works—they render genre distinctions unnecessary. Nevertheless, it seems that you are in constant search, not just for stories, drama and narrative.

Both in documentaries and fiction I look for a story and drama, and also, I think, for confrontation with reality or confrontations between different kinds of reality that are themselves a form of confronting reality. When two kinds of reality are confronted, a third kind emerges that doesn't exist in the film nor in the actual world, but in the viewer's mind, in the spirit of Eisenstein's montage. In Leibowitz in Maalot, I created a confrontation between the intellectual worlds of three thinkers and day-to-day Israeli reality, which isn't even remotely philosophical. In Pillar in a Cloud of Blood (a television film about Uri Zvi Greenberg), I confronted Uri Zvi Greenberg's poetry with current daily imagery of cinema and television. In The Guide for the Perplexed, the confrontation is between Maimonides' world and the 21st century reality. Even if I escape or pretend to escape reality, as in the fictional Etsba Elohim (2008), I try to face it, but not to accept it.

In Letters to Felice, why did Kafka have to meet with people in that restaurant in Bat-Yam of all places? Generally, it you seem occupied by Bat-Yam, its architecture, the solar heaters on the roofs, its crowdedness, its people. You filmed three or four movies there.

Something about Bat-Yam is like the kibbutz of the 1930's and 1950's, a kind of Israeli essence.

What is the essence of Israeli-ness?

Life breaking out of the concrete enclosures, a combination of sea, sun, asphalt, concrete, innocence and aggressiveness. Michal Aviad captured it very nicely in Jenny & Jenny (1997).

What fascinates you about creating these encounters between Jewish thinkers outside the Israeli sphere and concurrent Israeli reality?

You have to know the other in order to know who and what you are.

You make them meet the here and now as you meet it. You too are not a product of Israeli reality. Like these texts that you write, you came from the west to the east.

From England, where I was born, to Eastern Europe at first, Poland. My parents thought they would build a socialist state there. I was eight. I didn't speak a word of Polish, but I grew up with a portrait of Stalin in the living room. After he died, my parents tied a black ribbon to the corner of the portrait. At that time, you couldn't ignore the discrepancy between the communist regime clichés and the actual state of affairs: poverty, misery, drunkenness and anti-Semitism. And I still see this discrepancy, in a slightly different version, here today, here too… So to answer your question, maybe it's true; perhaps my films are a continual reckoning: Was it right to come here? My family came to Israel very much on account of my insistence. There were other options. My father, who was a scientist, a chemist, was offered positions in England and in Austria. Was it right to drag them here? Was it responsible? To have children here? I still think (mind the word “still”) that it was right. Not because Israel or Bat-Yam is so beautiful, but because of the ugliness of the Europe I knew in the 1950's.

I would like to pursue the biographic line further. Tell us about your encounter with Israel, with Zionism.

When my parents were contemplating where to migrate to, I announced that if they would not go to Israel, I would run away from home to go there. I was very determined. I wasn't raised with Jewish traditions, and yet I felt that in any country but Israel I would still be Jewish. I knew nothing about Judaism. I pictured Jews as curly haired people, detached, alienated, whiny. I am probably the last of Herzl's followers (laughing). He too wanted Israel for the sake not of being Jewish, but of being normal. I realized, and I think I was right, that Israel is a place where everyone is curly-haired, detached and alienated, so there I would no longer be detached and alienated, maybe just curly-haired. And as for the whining, I guess I was wrong, no nation is whinier than the people of Zion.

I came to Tel-Aviv in the middle of 11th grade, not knowing any Hebrew. My English was bad too, because I had forgotten it. In Poland, the children called me “English”. I hated that nickname, and in trying so hard to become Polish, my English was obliterated.

How did you end up in cinema?

(laughing) Like any other good-for-nothing: if you can't be a scientist, a writer, an economist, you go into politics or cinema. I had already been burned by politics, so I chose the latter. I take solace in the fact that cinema causes less damage than politics. My father used to say that Israel was a sinkhole for ineptitude – those who come here are those who can't find a place in the US, Canada, France or Denmark. The passion for cinema is probably like the passion for Israel, the passion of good-for-nothings.

At 16, when we came here, I had the fantasy of being a sort of Hemingway, with a pipe in my mouth and a hunting rifle on my shoulder. But I didn't speak the language. I started studying mathematics, a field for which I am really not good. One day I saw Blow-Up and decided to become a cinematographer. It was my understanding that cinematographers, unlike mathematicians, are athletic, handsome, rich, and that they ride around in sports cars with beautiful models draped around their necks, gazing at them with admiration. It didn't work out that way. There were no models, and I never became a cinematographer. I studied for just four months at a cinema school in London. I came back when the Six-Day War broke out to join my artillery battalion, which was already deployed deep in the Sinai desert. I curtailed my studies because I got a scholarship, and made a short film, Louise, Louise. It won awards, and the rest is history.

Another recurring motif in your works is the interplay between sound and image. You put a lot of thought into it, and it keeps resurfacing over the years. What are you after?

It could be that the conflict between abstract ideas and a reality that denies them makes the sound, which is always more abstract, contrast with the image, which is, at least apparently, always concrete. In Mohamed Yiktzor, a 1976 television film, if you remember, classical Zionism, using quotes from A.D Gordon, Ahad Ha'am, Ussishkin and others of their generation, faces the Zionist activity filmed in Rafah and in the tobacco plots of the Jordan Valley. Eight- and ten-year-old children from the occupied territories and from Arab villages were employed in fields owned by Jewish contractors from Metula. A similar thing can be said about your film (Ran Tal's Children of the Sun, 2007). Only in your case it is reversed. The soundtrack is concrete, concrete people responding to the event, manipulated, embellished and transformed by images, mostly filmed journals and Zionist propaganda films. In Anat's Achrey Hasof (2009) too, there is constant conflict between the voice of an unseen teller and the image shot from her window, which has hardly any relation to the spoken narrative. Conversely, in Luise, Luise, my first film, and in Etsba Elohim, my last one – both of which are naïve or striving for naivety – the sound, including the music, is synchronic, and the sound-image interrelations are naive, or striving for naivety.

Back to Letters to Felice, you have Kafka meet with the Bat-Yam people in a cafe. It looks completely documentary, but it is in fact completely scripted and directed?

If you look closely, you can see that few of the shots are too perfect, with mise-en-scenes that are too precise. Two scamps saying goodbye to a girl they are wooing, the camera moves sideways and in perfect timing three boys start badgering three girls leaning against a metal banister. It all happens in precise timing, which would surely give away, to an expert eye, the fact that it's directed. We planned, Era Lapid the wonderful (!) editor and I, to disrupt it through editing, so it would look more incidental and documentary. But the shot was so impressive that we couldn't bring ourselves to do it.

The idea to juxtapose Franz Kafka with the people of Bat-Yam was conceived on one evening I spent in one of the bars situated on the promenade there. People were getting drunk, singing, making out, kissing, dancing on tables. In their being carried away with the music, in the thick erotic atmosphere, in the relations between people, in the extrovert joy, there was something desperate, like a prisoner locked up most of the week in a small stifling dungeon being released for a moment. Kafka on the other hand, is a sort of spoiled middle-class dork with ego and communication issues. I know that Kafka liked to hang out in cafes like that one. He liked to party and suffer. Usually he suffered. Prague had these cafes, like any place where destitute people live. For months I would go there, and if I saw a character, man or woman, who reminded me of the original evening that I wanted to recreate, I would ask for their address. Later, I met with the people I had singled out for rehearsals of sorts. We would meet in the cafe and work out together what each of them would do in the filmed evening. At the same time, I edited pieces from Letters to Felice, a collection of love letters written by Kafka to Felice Bauer at the beginning of the 20th century, passages from his diaries, and some excerpts from Letters to Milena, his subsequent lover. The contrast between the middle-upper class Kafka and the lower class Bat-Yam population made for two opposite dynamics: the filmed evening starts with a cold, alienated atmosphere and ends with a kind of orgy of rapture and passion. The Kafka texts go the opposite way: from passion to the depression of solitude. All of this was integrated in the script describing an imagined evening based on the original evening I had happened to witness by shear chance.

So everyone knew their roles that evening, and reality seeped into the events?

Some of the characters happened to walk in, but most were invited. The boy who hit on the girl came from the youth theater, Peace Child Israel, managed by my ex wife Yael Druyanoff. Some of my students also participated in the film. As kind of assistant directors, they mingled with the audience and distracted the non-actor actors from the camera. A band of rapscallions stepping out of dented Renault 4 arrives in my car, in an utterly directed scene. I wanted them to keep getting out continually in one shot, but unfortunately something in the filming didn't work, and we had to make a cut there that pains me to this day.

We worked with two cameras. The cinematographers were Jorge Gurvich and Roni Katzenelson. The filmed personages entered the bar according to set timing so that they could be recognized and maybe also empathized with, and so that the photographers would know when to start shooting. We shot with 16-millimeter film. Technical supplies were the chief expense in this kind of production. We had to be economical. As the evening evolved, I lost all control, over both what was happening and the supplies. But the events were already self-propelled, and the cinematographers knew how to handle it.

Did you also select the singer who sang there that night?

Doron Miran. I saw a few singers, and chose him. He is very expressive and very well liked by the Bat-Yam bar crowd.

Was it all shot in one evening?

No. We filmed one evening, and then there were two days of gap-filling with the same people. We reconstructed positions already filmed and focused on details, accentuations, close ups, various elements to be used for editing.

Why didn't you just film a documentary?

If I had waited for things to happen, I doubt they would have. And if they did, they wouldn't have happened in the three days of filming at my disposal, but in thirty. My patience was limited, like the budgets I work with. I don't have the patience to wait for thirty days for something interesting to happen. Even if interesting things happened, we would relate to them less because they would not happen to the same people. Three days with ten familiar people that you can identify with will always be more succinct and intensive than thirty days with a hundred anonymous people. As Petronius said to the emperor Nero when he had an orgy with 100 women: “One naked woman impresses me more than a hundred naked women”. If we filmed the same ten people for thirty days, brining them to the cafe every evening for filming, after two days we would know what to expect of them, and the result would have been just as directed as that made in three days.

Since you mentioned Jorge Gurvitch and Roni Katzenelson— at the start of a project, how do you approach the question of cinematography?

I talk to cinematographers a lot, trying to delineate along with them the film's style. In Letters to Felice, I asked them to film at eye level, never from above. If people are sitting, to sit in front of them, if they are dancing, to move with them, if they look at the camera, not to cut, but to look back, to film with as narrow an angle as possible, but not fanatically, meaning that if there is an interaction going on between two people, open the lens up so as to fit both in the frame. In short, to identify with the characters and go along with them. It is obvious to me, whether in a documentary or in a film like Letters to Felice, that you shouldn't intervene while filming because it ruins the characters' spontaneity. The photographer has to be autonomous, to take immediate decisions in real time. In most of my films, the first and foremost role of cinematography is to serve the actors and advance the story. I am quite conventional in that respect. And in some films, such as Everlasting Joy, the photography is a result of a compromise with reality. We pictured it, Jorge and I, as a blindingly bright, sweaty film, just the opposite of the dark and subtle Dutch paintings. We wanted a lot of light, the over-exposure whiteout, lens flares. But sadly we did not go all the way with it.

Why didn't you go all the way?

Because it turns out that styling – even in an overtly careless style – takes time, which we did not have in that production. Flashes, lens flares, various kinds of shimmering from cars, roads, white-washed neighborhoods, all require controlled lighting which is always time consuming. With regards to this choice between story and style, for Everlasting Joy, I chose the story. In retrospect, I regret it a little.

This interview revolves mainly around the aesthetic choices you make in your films, but they can't be separated from the content, from contexts of time and place. Would you say your films are political?

It depends on your definition of political. If you show a struggling Israeli world, sweaty, sun-scorched and violent, you are perforce “political”, certainly in the view of those who seek idyllic imagery that would encourage tourism and emigration from developed countries. As for political conflicts in the usual sense: the Jewish-Palestinian conflict, disparity, the conflict between Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews etc. I try, not always successfully, to circumvent them, at least in recent years. In the 1970's and 80's, especially in Mohamed Yiktzor, Leibowitz in Ma'alot, Ethics, The Passion of Dr. Wider and Villa – the latter two are episodes of Israel 1983, produced by Tzavta in response to the occupation – I felt more committed and “political” than today. I find that the more I take a political stand in a film, the more I wallow in clichés. I believe that politics, like love, the desire to make money, affection for animals, the urge to become famous, is an excellent motive for making films, but one that's a concern of the filmmaker, not the viewer. The filmmakers' motivations and the product they yield are two different things.

In most of your films you make the men a little shabby while women are serious, strong, practical.

I probably like women better than I like men. Maybe it's because I'm not crazy about the state of the world, which is still dictated by men. It's not that I'm sure that it would be any better if women were dictating things. In a reality dictated by women, I probably would make films with somewhat shabby women and serious, strong practical men

Let's talk a little about the word “career.” Do you really feel that despite doing so much you always seem to be left out eventually?

Like any filmmaker, I want people to watch my work and respond to it. Most of the films we have been talking about here – Letters to Felice, The Guide for the Perplexed, Zimzum, Mohamed Yiktzor, The Passion of Dr. Wider— are unavailable for viewing. I offered them to The Third Ear, but their buyer wouldn't buy them. He said he brought on Everlasting Joy a year ago, but no one was interested. I asked for a copy of Mohamed Yiktzor from the Israeli Television archives. My request must have seemed so ridiculous that they never bothered to answer. The Guide for the Perplexed, which has been aired twice on television, was never reviewed. No critic took the trouble to write about it, whether favorably or critically.

When I obtain a budget for a film, I am happy and pleased, but when I don't, I get really frustrated and angry! Then I write a furious and indignant book and calm down. Then I get angry again because no one reviews the book. Only one response was published about Intimate Gazes, a very advocative one, but essentially informative. No review has been written. That's it. No newspaper, no supplement wrote about it, no recension was written – silence, like after a bombardment. Many people think and write about cinematic theory, cinema critics and lecturers, but they all suddenly keep quiet. This book should have angered them, pleased them. I would expect there to be opinions for and against it. But nothing, they are all taking cover, reluctant to peep out. You can't leave thinking about cinema at the hands of fringe dwellers, including those at the fringes of cinema. Thinking about cinema is destined to dry out if there is no debate, intellectual fight, rival journals. These are its hormones and fertilizers.

So now what, what's next, what would you fancy?

Several funds have a script of mine, pending… So far, it has only been rejected…

What is it about?

It is based on Casanova's Homecoming, a novel by Arthur Schnitzler. The story takes place in the 18th century, and it is about the historic Casanova trying to return to his home town of Venice. I shifted it to 21st-century Jerusalem. The protagonist is an ex-journalist nicknamed Casanova for having been an avid womanizer in the 1970's. After 20 years abroad, where he and a Palestinian partner edited a periodical dubbed “Palestine Tomorrow”, he returns to Israel. The secret service want him to contact his former partner, who has affiliated himself with Hamas in the meantime. He is quite reluctant, but he is getting old, and he is tired, and he needs the healthcare organization to give him treatment and a way out of some debts he had accumulated in Berlin. He keeps avoiding the execution of this mission, in which, I am happy to report, he eventually fails. Unlike the original Casanova, who did rat out on the free thinkers of Venice in return for his repatriation, my hero fails the task he is given, not for ideology so much, he is already too cynical for that, but more for aesthetic reasons. He does not differentiate morals from aesthetics.

Is there a documentary in sight?

Not at the moment. I made documentaries for decades, and I am little tired of it. The almost inescapable voyeurism and the interference, which is also unavoidable, in peoples' lives bother me. Documentary films interest me nowadays only if they harbor the possibility of experimentation or if they can be made independently of institutions and funds. But right now I have no ideas along those lines. My creative passions are channeled in the meantime to another script. My protagonist is a farmer's widow in one of the Rothschild towns in the early 20th century. The baron's clerk manages to force himself on her, and she seeks revenge.

Can you say something about films that inspired you?

Any good film is a source for inspiration, even if it has no direct bearing on the outcome of that inspiration. In cinema there are directors I love deeply. But I can't say how much they influenced me, if at all. And still, it seems that if it wasn't for Jacques Tati I wouldn't have made Ethics, and if it wasn't for Godard’s and Allen Resnais’ documentaries (Night and Fog, All the World's Memories, Gauguin), I wouldn't have made Mohamed Yikzor, Pillar in a Cloud of Blood, Letters to Felice or Everlasting Joy, and without Bunuel, I wouldn't have made Zimzum. I also love classical, romantic cinema, like the films I watched growing up: Children of Paradise, La Strada, and— like everybody – Alfred Hitchcock's films. I had excellent teachers for sure. And as a pupil, I feel I haven't reached bar mitzvah age yet. Maybe someday I will.

לואיזה, לואיזה! (1968), מוחמד יקצור (1976), עמוד ענן בדמים (1980), לייבוביץ' במעלות (1981), יסוריו של ד"ר וידר (1983), וילה (1983), תורת המידות (1992), מכתבים לפליציה (1993), אושר ללא גבול (1997),זימזום (2002),מורה נבוכים (2005), אצבע אלוהים (2008).