Ran Tal interviews Duki Dror

We have been wanting to meet Duki Dror for some time. He has an impressive filmography, as seen on his Wikipedia. He has been a director on 23 films and a producer on 6 other films. He grew up in Tel Aviv, studied in the United States, and now lives between Binyamina and Tel Aviv. He has been working continuously for 25 years. Duki is obviously a director we should all be listening to, beyond just watching his films. In the past few years, Duki has undergone a change, looking for a broader audience and for platforms outside of Israel, which will allow him to reach an international audience. He gave me two hours before the premiere screening of his new film; “There Are No Lions in Tel Aviv” (2019), at the Docaviv Festival.

How did you start with film or photography?

Growing up in Tel Aviv, I started studying photography in 10th grade. During the first year I went to the beach and took pictures of sunsets. On the way there, I would walk along the Yarkon river, which was one of the more deserted places in the city, and I took pictures of scrap objects, dead animals and things washed up by the river along the bank. This process of holding the camera, taking photos, and then developing it, excited me. After my army service, I went to the United States and studied in Chicago and in Los Angeles, not just filmmaking, but also classical literature and theater. I was like a sponge that could absorb everything.

What sort of movies did you make in school?

Experimental, mostly.

Have you seen these movies recently?

Not really.

Don't you want to see them?

Not particularly.

It's interesting that you started with experimental films.

I was influenced by the French New Wave; Godard and Alain Resnais and experimental cinema, such as Norman McLaren’s abstract films where he draws directly on the celluloid film. I was exposed to these films for the first time and was captivated.

What did you take from studying in Chicago?

Chicago is a bit more European than Los Angeles. There were teachers who came from more experimental, European schools of though, or from the American Indie that is closer to Europe than to Hollywood. I studied with one of the teachers I most admired, Peter Thompson, an experimental filmmaker, who built unique cameras that transformed the films he made into plastic art. His work was far from practical and commercial, but, in his first class, he taught us how to use Excel and how to build a production budget. During my studies, this was one of the most important lessons I was given, because then I realized that, in order to make movies, you need to understand the economic aspect of film; how to produce and what it takes to produce. You must understand this, especially if you work as an independent filmmaker.

Later on during that course, I had to make a short five minute film. I was looking for a subject and decided to tell the story of a special program run in Chicago prisons: illiterate inmates were taught to read and write,by their peers. I arrived at the prison to meet the inmates and for the first time in my life, I interviewed someone for a movie. My first interviewees were convicted murderers that were given life sentences, and the experience was simply enthralling. Suddenly, I was asking questions, talking to people I would never otherwise meet. I had a conversation with them and was given a chance to understand their thoughts and their story. It’s an experience I hadn’t felt before when making scripted films, and it led to process that lasted a year and a half, which ended with an hour-long documentary; Sentenced to Learn (1993). It was a process that taught me a lot. The editing process was like writing a screenplay after filming. In short, it was work that I was really fascinated by.

The movie succeeded?

The film was accepted for the Cinema du Reel Festival, in the Pompidou Center in Paris, for a series called “Landmarks in American Documentary Film”. When I arrived, I met the American documentary filmmakers that I had just learned about: Al Meisels, Richard Leacock, Ross McElwee, Alan Berliner and others, whose films screened in this series. I presented my first movie there. My student film was shown alongside leading filmmakers and this was a formative moment in my career. I felt that I had found a genre that was very rewarding and gratifying, and which could lead to professional accomplishment in a relatively short time. I don't know what I would think about my film today. I'm probably a little scared to watch the movies I have made in the past, because I will only see their problems and flaws.

Why did you decide to return to Israel?

It wasn't the plan. The next movie I wanted to make was about Chicago blues musicians. But at the same time, having been influenced by my encounter with American filmmakers in Paris, I was sucked into a first-person documentary and I started making a movie about my dad and his two brothers. They had a menorah factory, which was about to shut down. Working on this film, along with my partner, who wanted to return to Israel, made me give up my life in America and return to Israel.

Have you ever regretted that you might have had an American life?

There was no regret, but the return to Israel was quite complex. When you are an immigrant, you are a traveller, leaving your home and your country, you can start to escape all kinds of demons that had haunted you from home. During my 20s and 30s, for maybe eight years of my life away from Israel, I developed and grew and changed. I was no longer the same person that left Israel. So, I feared that going back would be going back to all those demons. The day I left the US was the day of the Oslo Accords; September 13th, 1993.

What kind of demons are you talking about?

Personal demons, self-esteem, for example. As an immigrant you are anonymous. You start a clean page and you are not bound to the image you previously created for yourself or the environment you started from.

You chose to make a movie about family, so I guess it's also about your family demons. This is your most personal film.

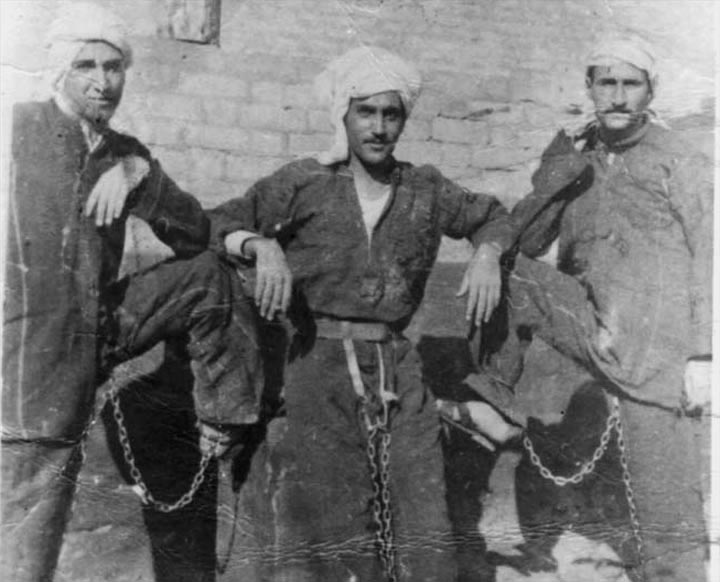

Right. I think one of my demons is my relationship with my dad. A lot of men experience

this. But especially if you live with a father, who was in jail for five years as a political prisoner in Iraq (on Zionist charges), who experienced abusive treatment. It affected our relationship. I used to try to escape it. Even though he gave so much love and needed his family, this man was traumatized from an experience that shaped him from age 17 to 22, and shaped our relationship. I wanted to escape that memory and the film dragged out those experiences with my father that I was trying to escape. I think the movie was some sort of an attempt to resolve my relationship with my father.

You've never done another movie like this.

Yes, that’s right, but a year after I came back, when I was trying to find my place back in Israel, one of the things that was kind of therapeutic for me, was curating a festival of first-person documentaries at the Tel Aviv Cinematheque. It was in 1994. I curated a series of twenty personal movies. I contacted David Perlov and told him that I was curating this festival of personal documentaries, and asked him to write the text for the program. But he became angry with me and said: “Listen, there's no such thing as a personal documentary. Every documentary is personal.”

Angry?

Yes. He was really pissed off, and didn't come to the festival.

The movie My Fantasia (2000) was one of your first works that started to deal with the Mizrachi identity.

Yes, one of the things that I grew more conscious of during my time in the United States was this notion of a Mizrachi identity. I wasn't aware of it before. At that time, it was clear to me that this was an area that interested me. I wanted to go deeper into it and understand it. I wanted to say something about it that hadn't been said before. So, through the story of my family, of the three brothers and the drama of their Menorah factory, and the relationship between me and my dad, that’s the way I tried to address it.

What did your Dad think of the movie?

He was very scared of the exposure. He tried to ignore it. It wasn't pleasant for him, but I think he later came to terms with it. Maybe it even did him good. Beyond just the difficulty of confronting my dad openly with this story, it was also not easy to raise money for the film. Not that it's easy to get funding for any documentary. But here, somehow, I had to work harder in every way possible, put in extra effort in order to persuade people that it was an important topic and a worthy film. I had to explain why it truly was important to tell this story. And by the way, to get funding for any of my films on Mizrachi topics is a bit like demolishing a wall with a sledgehammer. It was very, very challenging. For any of this to happen, iron, as they say, had to bend.

You do not seem to be a loyal soldier in the army of identity politics, as you have movies on so many varied topics. Which of your films are about identity issues?

Cafe Noah, a 1996 movie I made, was inspired by the Buena Vista Club, Wim Wenders' movie on Cuban musicians in Havana. I wanted to go back to similar old musicians, who came from Iraq and Egypt, in order to recreate what I had seen at the age of 13, at my bar mitzvah, when my parents had hired the Arab Orchestra. When I was 13, that was terribly embarrassing for me. But now today, I look at the same music in a totally different way. I see them playing the music that they heard and loved that I as a child hated, and I realized that it’s actually a high culture, which needs to be brought back out into the light. I submitted it for funding and it was rejected rather unpleasantly, I would say. They said it was “too folksy”.

Funders don't realise that we film`makers file all their rejection letters, do they?

Yes, I still have that rejection letter. The movie came out finally as a short half hour documentary, screened on Channel 2. Three days of shooting and seven days of editing.

Do you feel that this was a mistake, that the movie deserved better?

Probably. I'm glad that Eyal Halfon has now made Charlie Baghdad (2002), but when I filmed them, the musicians were still at the height of their musical power. They were still present and powerful, just before old age began to take its toll. So, it was important to make my movie. When the film came out, everybody said how glad they were that it had been made.

Then I worked on a sequel, which was also really difficult to find funding for; Takasim (1999). The sequel follows one of the musicians of Cafe Noah, searching for the lost recordings of his violinist brother in Cairo. Again, it started life as a half hour movie production for Channel 2, but ended up as a one hour film.

Your ‘eastern upbringing’ is not typical. You grew up in North Tel Aviv. I mean, this is not the typical experience of someone growing up on the periphery.

Right. I once talked to Yossi Sucari, who also grew up in North Tel Aviv, largely an Ashkenazi community, and we talked about the fact that this gave us an experience of ‘double exile’. I mean, you're screwed twice. You are both Mizrachi and yet you cannot be Mizrachi. You have to hide it. You try to integrate as much as you can. And of course, the thing people always say, in the end, is, "You don't look Mizrachi!"

Do your films about middle eastern Jewry have an Arabic-speaking audience?

Yes, Shadow in Baghdad (2013) has a strong audience in the Arab world. I feel it has had the most impact of all my films, because it went out beyond Israeli borders and into the Arab world. It has inspired a rare debate, in Iraq, and in the Jewish and non-Jewish Iraqi diaspora. The heroine (Linda Abdul Aziz Menuhin) is not only a character in the movie, she is also an activist on Facebook and other social media. So, a real dialogue has developed between Israelis and Iraqis, between Jews and non-Jews, on the basis of a shared history. For the first time, articles in the Arab press brought up the topic of the disappearance of Jews from Iraq as a tragedy, which influenced the whole country. This debate is the biggest reward for me, when I can feel the power of the documentary to touch people. The success of any movie is founded on its ability to move people on from square one to square two.

You deal a lot with Orientalism, but your influences and culture are really western. Is there a middle eastern aesthetic that you embrace in your work? Or is it mainly reflected in the narratives you cover?

First of all, naturally my influences are Western. We're all half Americans here in Israel, culturally speaking. That's the cultural diet we mostly consume. And of course, after eight years of living in the US, I absorbed a lot of American culture. But alongside that, I think I have something in the way I conceptualize, my worldview or the way I look at the world, which is different. Call it 'Oriental' if you want, it may be less analytical and more intuitive, more emotional. Currently I am working on a series about the Lebanon wars. I have no doubt that the cinematic language of the series is Western, but there is also something else that influences the content and style and gives this series a different tone.

But that's the political view. I'm talking about the aesthetic look.

And I'm talking about a point of view. You can call it a political view, but it's not. Maybe that implies a political ‘look’. Cinema is a platform, and, for me, it is a place to test human complexity, and through it, my own complexity as well. I don't think my job as a documentarist is to be a political activist, but rather to try and represent some truth, without pushing a political agenda that is convenient to me.

When did you make "Shadow in Baghdad"?

In 2013.

And you haven't dealt with those issues since?

I am dealing with those issues. I currently have a project at Tel Aviv University called “Oriental Express,” that focuses on the love-hate relations between Mizrachim and Arabs. I am dealing with other issues at the same time.

I'm trying to figure out who Duki Dror is as a filmmaker, and it is hard to put my finger on it. On the one hand, you started with a movie about your family and with a Mizrachi discourse. But you also made a film about children going to school (SideWalk, 2007), and a film about a young woman going back to Vietnam (The Journey of Vaan Nguyen, 2005) and a film about a boxer (Raging Dove, 2002). So there are lots of styles, lots of themes. Do you think you can articulate a connecting thread? I'm sure it exists.

I believe that content produces style. You have to understand the content, to go deeper and formulate an image, a premise, to get to the essence. Now you have a palette of colors and then you can say, OK, I can paint that setting in those colors and that content in those colors. There are lots of options. I don't want to set myself in one style, because that's the thing that I enjoy the most, playing with styles, checking them out, finding what fits precisely for the content and the premise. However, I think that if you put all my films on top of each other, you will see a similar shape that runs through all of them, more or less.

Can you define it?

I think it's the way I look at things, the characters, their story and how I build the cinematic syntax, each scene and between scenes. I was influenced by Joseph Campbell's books, about the story patterns of mythology; how there is actually one story that is told a million times in a million shapes. I think you can see that all of my films have a similar syntax and a similar way of looking at the characters and their journey, even if they are impressionistic films like SideWalk.

Lovely movie, by the way…

The same goes for Inside the Mossad (2017). Again, it’s the way I tell the story. It goes back to my first film, I'm in front of prisoners with a life sentence, interviewing them. What intrigues me is to learn about them, to see where the conversation goes, and how it slowly creates a story.

You tell the story, and the cinematic language follows…

Style is elastic.

You did not talk about the topics of the films. Is there a thread that runs through all the topics you are dealing with?

I am very attracted to people or topics that no one else will deal with. Unnamed, unknown heroes. People who have had or are having a very big impact but which no one notices, or topics that are not commonly dealt with. In my latest film, There are No Lions in Tel Aviv (2019), I reveal the story of Rabbi Shorenstein, from Denmark. Everyone has heard of the Tel Aviv Zoo, but most people have not heard the story of the man behind it. A man, who loved animals and had a dream to build a zoo, which he fulfilled, but from which he was later cruelly expelled. I'm attracted to these stories of dreamers, who have to fight against the establishment to fulfill their dream.

In fact, you also deal a lot with the experience of being foreign and of immigration.You called it “heroes without a name”. You seem to really like that there is a journey in the movie, and the journey is a journey of the mind. But of course, it’s also physical. I mean your characters have to go to Vietnam, Cairo, or go from school back home. They travel, they win boxing competitions, they go to Iraq, or want to go to Iraq. Your heroes do not sit at home. You want them to move in your cinematic world, either physically or mentally …

It's something within me, the ground is unsafe, unsteady. You have to be on the move all the time. You are constantly in motion. This is how I perceive my characters, they all are going through some kind of journey.

But you also have your own journey in this world. Your latest movie There are No Lions in Tel Aviv – does this relate to your Tel Aviv experience and perhaps to your dad?

It's more of a trip back to my childhood experience in Tel Aviv, on the rooftops above the city, right behind the zoo, that’s where my playground was. And that’s where I could have some space alone, away from my family. A space for contemplation.

At some point you also became a production house. Is this linked to the class on the Excel?

I attended a lecture by Frank Zappa at UCLA, at the music school. That's where he told the two hundred people listening to him in this hall, guys, if you don’t make music as your business, go out and get a real estate agent license… I was a bit perplexed at the time. But, then, I finally realized that ultimately cinema has to be an economic business, not just art.

So at some point, I created a production house, a boutique production house. I produced Ibtisam Mara’ana’s first film and several other films. There was something rewarding about not just dealing with yours own work. So I did dedicate myself to other people’s films from time to time. But I have now stopped doing that because I realized that being a documentary producer is a very dubious economic business.

Why?

That's just the way it is. I have now found something that replaces producing. I advise student projects, it's much less financially binding and I really enjoy the mentoring process. Thinking with the students, figuring out the creative process, which is difficult, and helping them in their search for solutions.

Your film about the architect Erich Mendelsohn (Mendelsohn’s Incessant Visions, 2011) is an exception in your filmography. Mendelsohn is a refugee, and he is always in motion, yet this time you're dealing with an Ashkenazi icon. How did you come up with the idea for a film about Mendelsohn?

I grew up in Tel Aviv and, to my surprise, in 2003, UNESCO announced Tel Aviv as a World Heritage Site. I looked at Tel Aviv as a very ugly, unsympathetic place, and I didn't understand why it was chosen for conservation. I was intrigued to understand what this was about. I started looking at the buildings, trying to figure out what was behind the peeling plaster and the soot. I started looking for the beauty and the aesthetic. So I talked to architects and that is how I first heard of Erich Mendelsohn. He didn't even build in Tel Aviv, but I was told: listen, he had a big impact on this place. I started searching for pictures and photographs of the buildings he built. Then I went to the Schocken library in Jerusalem. As soon as I set foot in that building, I felt like I was entering an artist’s work. The same year, there was a conference at the Van Lear Institute on Mendelsohn and I found out that not only was he a really great artist, but he also had a fascinating life story. He was someone who greatly influenced the spirit of the places where he lived, and his spirit is still alive in these places today. However, history hasn’t remembered him. His life story drew me into deep research for about seven years. For the first four years, it was an investigation into the amount of information that was available and needed to be studied. It was the equivalent, in my opinion, to studying for a degree in the history of German Jewry and the history of modern art.

How did you figure out how to shoot it? What was your source of inspiration?

My source of inspiration, as far as I remember, was the Canadian film Tina in Mexico (2002), about Tina Modotti, an Italian photographer, who grew up in Los Angeles, who moved to Mexico and became the lover of Frida Kahlo. She later died in tragic circumstances. She was actually the protege of Edward Weston, the famous American photographer. The movie is told through the woman’s character, as an apprentice of a great master. ,The cinematic work was so exciting, it was so beautiful. The film is built mostly from Tina's letters. It’s a movie that is character driven and historical, fascinating and exciting. So I thought maybe it was possible to make a film about a non-living character, because until then I had only made films about living characters.

So, for you, the key to the film about Mendelsohn was his letters?

Yes.

Without the letters, you wouldn't have been able to make the movie?

Probably not.

As the character is what is most important to you, is the character always the key into every film?

Absolutely, but in this film, the key was also in the male-female relationship; the tension between Mendelsohn and his wife Louise. She opened up all the doors to success for him. She was a beautiful muze, a German Jew and he was an Ostjuden, a jew from Prussia, an artist. She was much younger than him. But she had developed emotional intelligence and he was the classic egocentric artist, who moved between despair and uphoria. It was clear for me that the main story was the relationship between the two, she as his inspiration and he as the artist. Perhaps without her, he would not have created everything he did.

Perhaps, only SideWalk is different from all your other films, which are all character-driven. It's an observational movie, where you don’t go into the psychological journey of the characters, and only look at their physical journey. This is actually your most impressionistic film.

Yes, indeed. But for me, at the symbolic level, all seven characters in the film converge into one character; a child. Each child represents a particular layer of this child, created from all of them.

In the past three to four years, you have also dipped your toe into television, and you have also changed your cinematic style. Is it an economic decision or are there other things that you want to look at, in terms of how to tell a story?

There are two things to discuss here. Many times, something that you see or hear intrigues you, so you start digging a little and suddenly you find a story that you must tell. And then you find yourself invested in a project for years, which was only begun by chance, innocent and unintentional curiosity. That's how it was with the Mossad series. The process began with a conversation I had with a man whom I interviewed for Shadow in Baghdad, and it evolved from there. Curiosity overwhelmed me quite quickly. And we discussed earlier, all of the Mossad's spies are unnamed heroes and this is what attracts me to a project,. So, obviously I wanted to make it. I also realized that there has never been a series about the psychological apparatus of Mossad agents, which is of course a “sexy” subject. So it had commercial potential. In retrospect, the idea to make a series like this, encouraging more than twenty Mossad agents, who live in the shadows, to talk in front of a camera, was quite naive. There was a certain kind of innocence and lack of awareness of what it meant and how complex it would be. But it worked out in the end. From the material we shot, we made a ninety-minute film and a four-episode series. The film was screened on Arte Germany and France successfully, bringing with it a high rating. And when it aired on HOT8, it became the most watched series they ever had. Then Netflix bought it and now it is broadcast everywhere in the world. This story pushed me into a whole new sphere, in terms of exposure, and also in terms of the publicity and reviews generated. And more recently in terms of an understanding of what I want to do next.

So, what DO you want to do next?

Many things. Mostly more series, because their dramaturgical construction intrigues me. Right now, I’m working on a series on the Lebanon Wars. It’s a coproduction. I understand that my audience is not just Israeli, so I want to appeal to the wider world but with content that is from here. You know, there is a glass ceiling here, and I aspire to constantly break through it.

In what way did you approach the series Inside the Mossad?

The visual approach was challenging. I didn’t want to do recreations, but rather to create symbolic images and scenes that play with the text. One of the things I have changed during the past few years is the way I work. From a small team, sometimes a one man band, the work process has become broader, and today I work in a totally different way. I have a producer, who is in charge of the entire production. I'm not engaged in production except for contract signing. This sharing of the workload gives me more space. I work with a bigger budget due to co-production, and that allows for a different process with a larger team. Many times, in the past, the budget has run out and I have had to use my skills as an editor, in order to finish my films. That’s how I survived financially and why I haven't gone bankrupt. In recent years, I have stopped doing it. Instead, I find the most talented people to work with.

And are you happy with where you are today?

Yes. The teamwork is very gratifying and enjoyable.

And how is your dialogue with the broadcasters, in Israel and abroad?

I have had a respectful and productive dialogue in recent years with my commissioning editors. I feel that they are my partners and they have a shared responsibility for the films. In the past, it would have been traumatic for me to share a rough cut screening with the commissioning editors, but today I see it as an advantage. In the end, the DNA of a project, whether a movie or a series, is the storytelling and the dramatic moments, and if that works well, then it will work for the audience. If the viewer understands the drama, the conflicts and dilemmas of the characters, then the story becomes universal.

You have a fascinating and broad filmography. I've counted more than twenty films. I understand you want to have a larger audience. But what movie do you dream of at night? What movie do you feel you must make?

I can hardly remember my dreams. But when I'm in the final stages of a film, I feel like I'm editing and putting scenes together in my dreams. I resolve editing issues that I have struggled with during the day, but in the morning I can't remember anything!

There are a lot of movies I want to make, and there is a movie that I keep postponing, but I know I will do it. It is a story about my uncle, who was a combat pilot in the Iraqi Airforce, in the 1930s. He was the only Jewish pilot. He had to change his name to a Muslim name to be accepted as a pilot. He was a close friend of the Royal Faisal family and the Iraqi princes. His story is amazing and is connected with the history of modern Iraq, British colonialism and the Farhoud, the massacre of Baghdad Jews in 1941 towards the end of World War II. A few years ago, I received three full albums of pictures showing his turbulent and amazing life, and one day it will become a movie.